The roots of racism

May 2021 marks a year since the murder of the 46-year-old black American George Floyd. On that occasion, we have taken a look at our collections to examine the roots of racism.

The video footage of the white cop with his knee on George Floyd's neck spread like wildfire around the world in 2020 and roused the anti-racist movement, Black Lives Matter. A year later, the movement is still active both in Denmark and in the United States. It is a showdown with police brutality, and what the movement calls structural racism.

Racism has a long history in the west - also in Denmark - so join us in the hunt for Denmark's past in the library's collections and learn about our part in the history of racism, and about how colonialist thinking has survived in Danish society throughout history.

It all begins

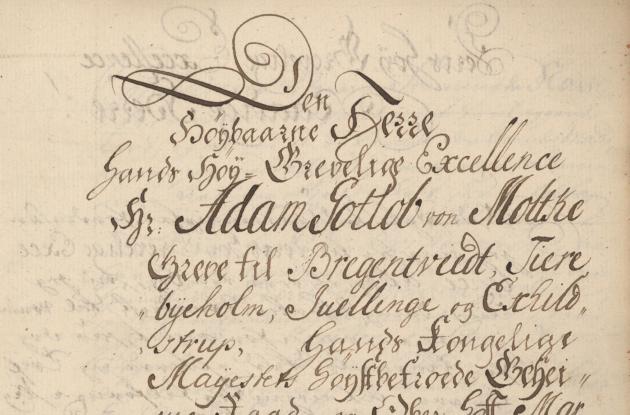

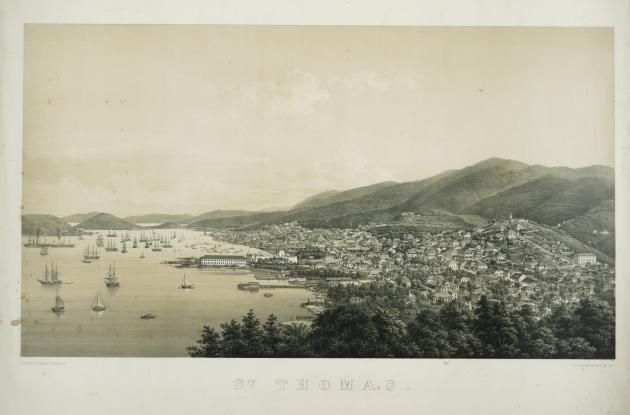

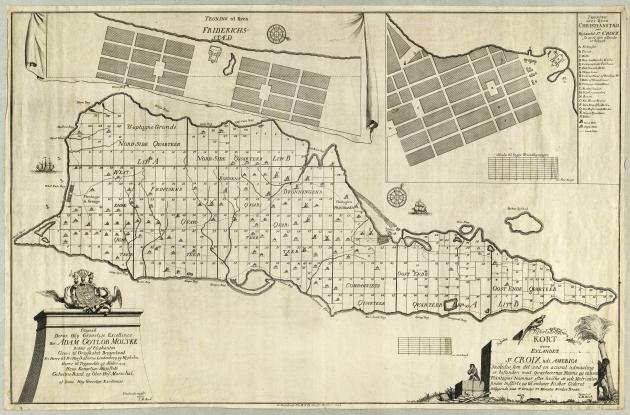

Our story begins late in the evening on 25 May 1672, when the Danish ship Færø anchors off the West Indian island of St. Thomas. At the ship's railing stands the 33-year-old Jørgen Iversen, who has been appointed as the island's first governor. Iversen and his companions go ashore and immediately begin to transform the lush landscape into sugar and cotton plantations. It is a proven economic model. England, France, the Netherlands and Spain are already underway. But the model requires one thing that Iversen does not have on his ship. Slaves.

What the other nations have already discovered is that it is difficult to get labour for the hard and grueling work on the plantations, so to run them at profit, one needs slaves.

It is in the hunt for labour that Iversen in 1674 sends the order for African slaves to come to the colony's plantations. During the following century, more than 120,000 enslaved Africans were transported across the Atlantic on Danish ships.

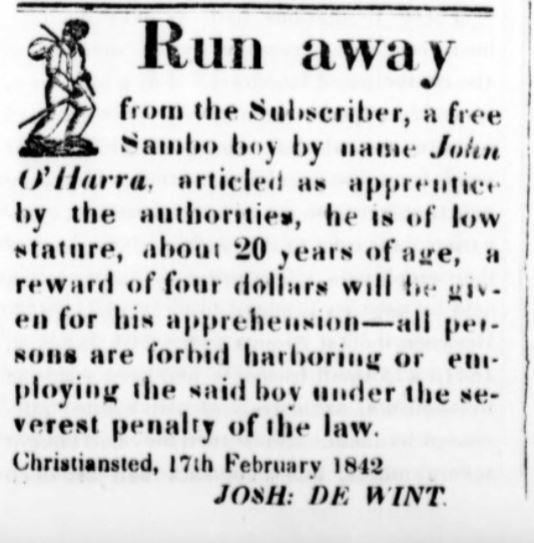

Photo: Dansk-Vestindisk Regieringsavis

"A well-fed creole"

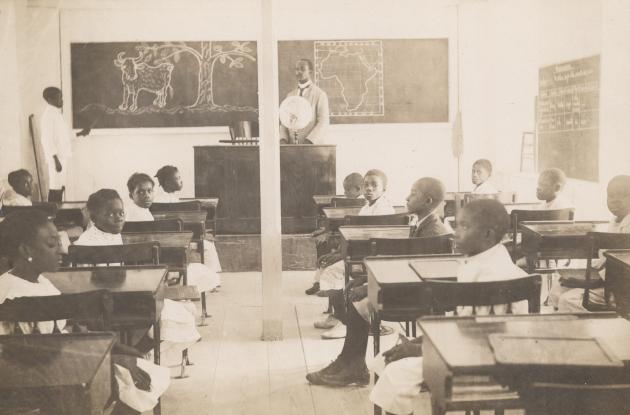

Most slaves' daily lives consist of hard work in the sugar cane fields, while others work as artisans or servants.

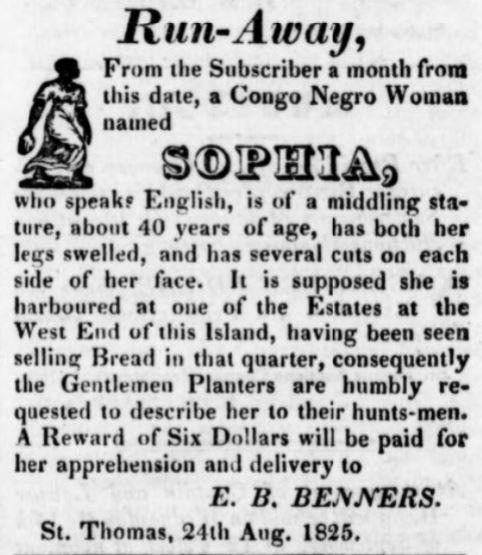

Running away is a widespread form of resistance for the enslaved. That slave escapes are common can be ascertained by searching the West Indian newspapers that we have digitised. They are full of wanted ads.

The wanted ads are examples of how plantation owners saw black people as possessions in line with cattle and pigs that could be described as "well-fed" or categorised into sub-races such as "sambos" (descendants of Indians and Africans) or Creoles (a slave boy born in the Caribbean). Meanwhile, those who tried to bring them back to the plantation are called "huntsmen". The ads describe the enslaved as animals. They are not "real" people.

Photo: Det Kgl. Bibliotek

This categorisation is necessary to justify slavery, for from the very beginning of the colony the moral right is questioned in the treatment of the enslaved. One of the ways to get around these issues is by considering the enslaved as in a separate category. They are morally depraved, primitive or animalistic, and therefore they deserve their fate.

Reimert Haagensen, who came to the Danish West Indies in 1739 and later became a leading plantation owner, published an account of the islands in which he made it clear that slaves all (were) evil

, their black skin

, wrote Haagensen, reveals their wickedness, and that they are destined for bondage, so that (they) should have no freedom

. This way of looking at the enslaved - and by extension all of those with dark skin - spread from the colonies to Europe - and Denmark was no exception.

You will find Haagensen's description here: R. Haagensen: Description of the Island Saint Croix in America, 1757 (in Danish).

After the abolition of slavery in 1848, these notions helped to justify why the African-Caribbean population had lower economic and social status than the white population. The notions did not go away, even as slavery did. Maybe one can even trace some of the notions to how we view Africans and African countries today?

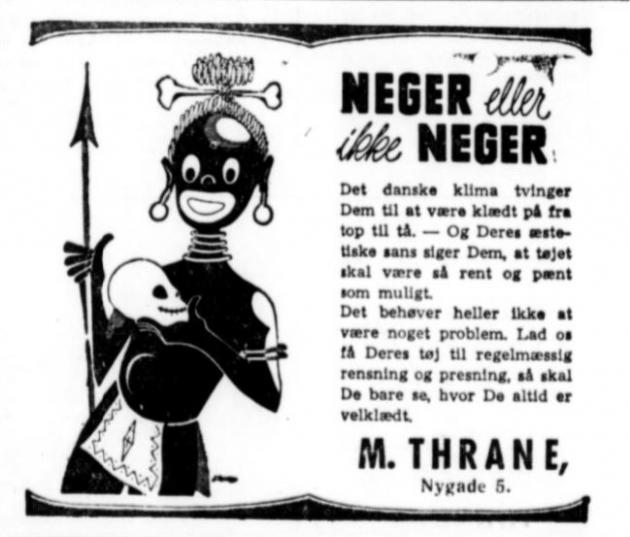

As much a Negro as one can ask for

At least that is the point the Black Lives Matter movement is making. That the life of black people - consciously or unconsciously - is considered less valuable than that of white people. And it is unfortunately not difficult to find examples of people with African roots being mentioned animalistically in Danish newspapers long after the abolition of slavery, just as they were in the wanted ads in the West Indian newspapers.

When Louis Armstrong performs for the first time in Denmark, his voice is described as guttural and his performance as animal. One reviewer even describes him as as much a Negro as one can ask for

.

Read for yourself with: Black Jazz ecstasy in Tivoli's Concert Hall (in Danish).

Photo: Det Kgl. Bibliotek

For most of the 20th century, there are very few black people in Denmark. We meet them in the newspapers as artists or musicians visiting from other countries. And yet black people often appear in Danish stories, advertisements and satire drawings, where they are often characterised as or seen as representatives of the primitive, uncivilised, almost animalistic. It is these images and not least the effect of them that Black Lives Matter is protesting against.

Learn more about the Danish West Indies in our collections

We have digitised most materials about the Danish West Indies in our collections.

Images from the Danish West Indies

Newspapers from the Danish West Indies

Map of the Danish West Indies

Prints from the Danish West Indies

Texts from the Danish West Indies