When married women became taxpayers

It was not until 1970 that the tax legislation was changed so that married women had the right to pay tax on their own income. Before, the husbands had been taxed on the their wives' income.

“Away with the tax on the marriage certificate. The state should not benefit from a man and a woman falling in love and getting married”.

This is how it sounded at a happening in Parliament in March 1968 with the participation of all 19 female members, many of whom were affiliated with the women's movement. The action was an attempt to put extra pressure on Parliament to change the gender-discriminatory tax legislation, which still perceived the husband as the head of the family and the main breadwinner, and the wife as the one who took care of the work in the home and therefore needed to be supported.

Specifically, it was about the fact that married women, roughly 70 years after gaining legal capacity in marriage in 1899, were still not taxed on their own income. Their husbands were! In practice, this was done by putting the wife's income on top of the husband's income, and then he paid taxes for both of them.

The main objections to joint taxation (as it was called) had both a gender equality and economic perspective. Economically, because the marriages where both had paid employment were taxed harder because of the proportional tax than if the couples were not married. Gender equality, because the tax legislation did not define married women as independent citizens.

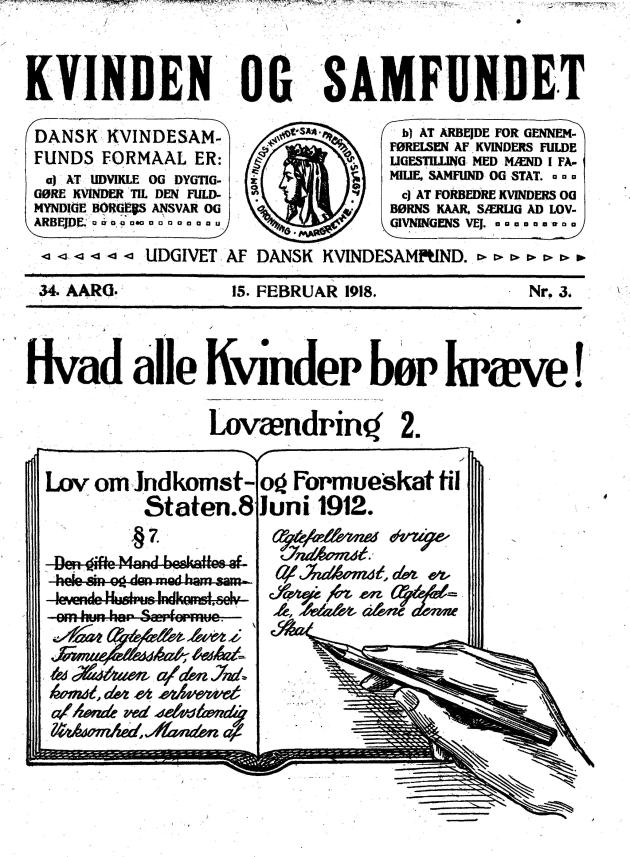

Photo: Kvinden og Samfundet

Difficult getting the law changed

The Danish Women's Society had already addressed the problem with a request to Parliament back in 1915, and at the election in 1918, which was the first election where women could vote and run for office, where the abolition of joint taxation was included in their questions to politicians. Afterwards, they tried again and again to bring the issue to attention, both with inquiries to Parliament and by writing letters and publishing pamphlets. All without result.

At the election in 1960, one could find ads in the Danish Women's Society's magazine "The Woman and Society" from the various political parties, where they all promised to abolish joint taxation. But nothing happened. And although the Danish Women's Society launched a signature campaign in 1963 with 70,000 signatures to support the demand, and five years later the female members of Parliament created a 'happening' in Parliament, it was only with the law on withholding tax in 1970 that married women could finally be allowed to pay tax on own income. However, the last remnant of joint taxation did not disappear until 1983.

When politicians hesitated for so long to introduce special taxation for married women, it is probably because the problem only became really clear to many of them during the 1960s, when married women flocked to the labour market. In 1960, there were approximately ¼ million married women in the labour market. In 1970, it was ½ million, and in 1979 ¾ million. This meant that the family construction on which joint taxation rested was disappearing. The single-parent family with a working father and a stay-at-home mother were replaced by the two-parent family, where both spouses had paid work. And that made the discrimination of the married woman in the tax legislation both very clear and completely unavoidable as an issue.