Nielsine Nielsen

Nielsine Nielsen fought her way to school and became the country's first female student. Her memoirs provide a unique insight into the early years of a more open university.

Photo: Ukendt.

He operated with oilcloth cuffs on, so you can see that antiseptics were not his strong suit.

This is how the young Nielsine Nielsen describes Professor Mathias Saxtorph. He taught at the medical school at the University of Copenhagen in the early 1880s, where Nielsen studied.

Nielsen stood out among her fellow students, as she was one of only two women at the university.

In her memoirs, Nielsine Nielsen describes her experiences during her studies, and she does not mince words. This can be seen, among other things, in her descriptions of Professor Saxtorph. When you read about her path and the resistance she encountered from Saxtorph himself in connection with admission to the university, you better understand the background to her criticism.

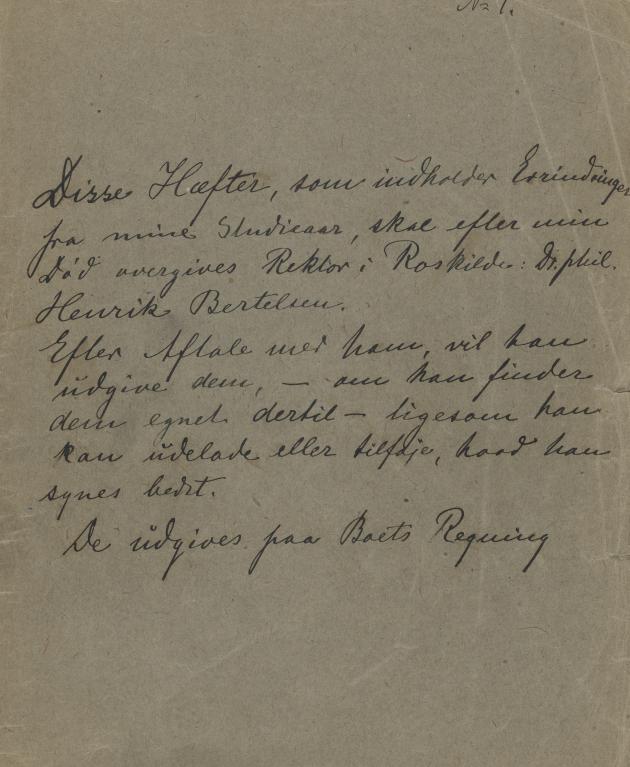

Read Nielsine's Memoirs here:

Photo: Nielsine Nielsen (1850-1916).

Nielsine Nielsen led the way and paved the way for other women who also wanted to study at the university.

In 1870, she was sitting at home in her parents' living room reading Nationaltidende. There she read that:

Ladies in America [had] begun to study medicine, and in one of the states it had even gone so far that a lady had established herself as a doctor.

This was the starting point for Nielsine Nielsen's own long struggle to get the opportunity to pursue an education.

Nielsine Nielsen's memoirs paint a picture of a young woman who was bookish and often read books. Reading was a passion she shared with her sometimes tyrannical father. Although she was later accepted into medical school, it was botany that interested her. But most of all, she possessed a thirst for knowledge that ultimately led her to apply to be enrolled at university.

Photo: J. A. Braae (1842-1924)

To gain admission to the university, Nielsine Nielsen had to write an application to the Ministry of Church and Education. The ministry forwarded the proposal for consultation to the university's faculties.

In April 1874, the Faculty of Law and Political Science issued the following statement:

According to the existing system, the woman has no legal right to appear for matriculation at the university after having fulfilled certain conditions.

Finally, the application ended up at the medical faculty, where there were both advocates and opponents of the admission of women. Most prominent was Professor Saxtorph. He was both in principle against the admission of women to the university and specifically to the medical school. In a party submission to Nielsine Nielsen's application, he wrote, among other things:

[...] I take it for granted that one should oppose everything that draws a woman away from the task that is destined for her by Providence, since it is already evident from the difference in sex that a woman's destiny is only fulfilled as a man's wife, that her calling is in the home and in the raising of the generation, I would find it most wrong if one would contribute to providing her with access to activities that lead her away from her rightful place [...]

But despite this resistance, women were granted access to universities, and Nielsine Nielsen was able to paint a less than positive picture of Saxtorph in her memoirs.

After Nielsine Nielsen graduated as a doctor, she opened a private clinic, which she ran until her death in 1916.