When women were allowed to enter the university

2025 marked 150 years since a royal decree allowed women to enter the university as students. This was a significant step toward equality.

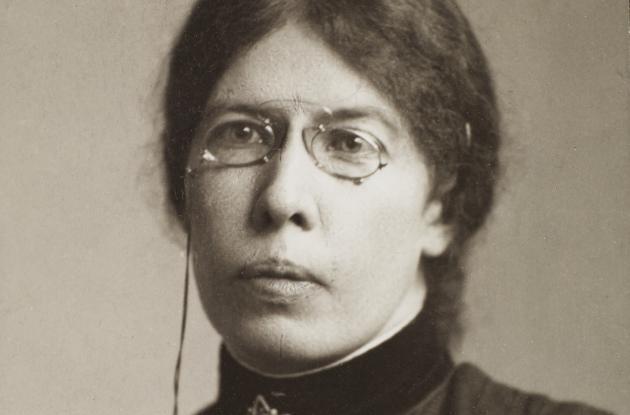

Photo: Julie Laurberg (1856-1925)

Nielsine Nielsen (1850-1916) from Svendborg was actually a trained teacher. But when she heard stories about female doctors from abroad, she was inspired. She also wanted to study to be a doctor. There was just one problem: at that time, women were not allowed to enter the university in Denmark.

Therefore, in 1874, she wrote to the Ministry of Church and Education and asked to be allowed to be admitted to medical school.

The ministry was positive about opening the university's doors to women. They sent the proposal for consultation to the various faculties. The university as a whole responded positively. This gave rise to King Christian IX's ordinance in 1875 to open academia to women.

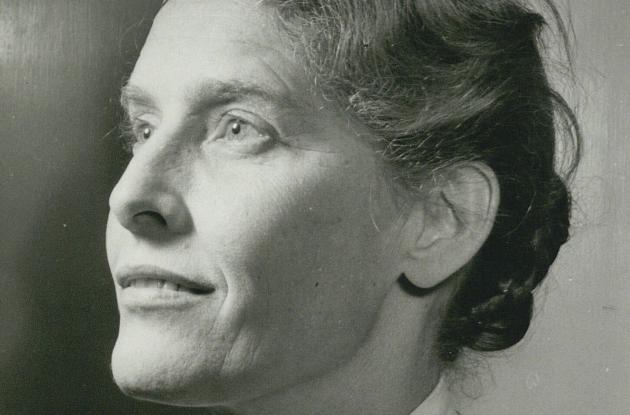

Photo: Lars Peter Elfelt (1866-1931)

This meant that women could now take exams in all subjects, except theology, at the University of Copenhagen.

To be admitted to the university, a Leaving Examination of Upper Secondary Education was required, just like today. The only problem was that in 1875 women did not have access to public Danish upper secondary schools. They did not get this until 1903. Instead, they had to study for their Leaving Examination themselves or apply to one of the few girls' schools - for example Natalie Zahle's, which offered upper secondary education from 1877.

Photo: Holger Damgaard (1870-1945)

Women were also not allowed to apply for university scholarships or access to the halls of residence. And they had no right to use their degrees in the public labour market afterwards. They did not get this until 1921.

There were also a few university professors from medicine and theology who were very critical and outright opponents of women in academia.

One of them was doctor and professor Mathias Saxtorph, who thought that it exceeded all decency and morality with female doctors. In his minority opinion, he wrote, among other things:

But what especially urges me to oppose with all my might the intrusion of women among the medical students is consideration for them and the general sense of decency. A woman who can disregard every sense of decency and modesty to such an extent that she can wish to attend lectures with the students on the anatomy and diseases of the male body, and who can be willing to examine and treat the surgical and syphilitic diseases of men in the respective hospital departments, can only be regarded by the students with loathing and disgust.

Another was the head of the theological faculty, Henrik Scharling. He did not believe that women had anything to contribute to academia, either now or in the future:

As for the matter in general, of giving women access to university lectures and examinations, we have no confidence that this will yield any significant benefit, either for the advancement of science, the spiritual development of mankind, or any real improvement in the condition of women.

Photo: Lars Peter Elfelt (1866-1931)

According to him, the woman's primary task should continue to be to take care of the reproductive work in the family as mother and wife. A task that was incompatible with playing a role in public life outside the four walls of the home:

The more the woman is drawn away from the family to an outward activity, the more will family life be weakened and dissolved, and the loss thereby inflicted on society will be as incalculable as it is irreparable.

Despite the concerns and objections, Nielsine Nielsen was able to enrol at the university in 1877 after taking the exam for upper secondary education as a private candidate. Eight years later, she completed her medical degree. She thus became the first female academic and the first female doctor in Denmark.

Discover the stories of the first female students:

Anna Hude

Clara Black

Karen Harrekilde-Petersen

Kirsten Auken

Kirstine Meyer

In an historic perspective