Meet Bolle Willum Luxdorph - one of history's unknown heroes

Had it not been for Bolle Willum Luxdorph and his prescience, the 18th century equivalent to Facebook might have disappeared forever. Get comfortable and read his story here.

We must go back to a winter's day in 1766 to find the beginning of the story. On a balcony at Christiansborg stands a confused and slightly freezing 17-year-old man, the future Christian VII, surveying his people. He is about to be proclaimed king, but the young man is really a tragic figure.

As a child, Christian VII seemed to be a promising heir to the throne, but everything that was promising about him, his educator, Ditlev Rewentlow, beat out of him, and the young prince's escalating mental problems did the rest. It is probable that Christian already suffers from schizophrenia at 17.

The young king waves his hat in greeting, the crowd cheers, and he retreats to the castle. In the coming days, the king succeeds in receiving the foreign envoys and Danish subjects without issues. Christian acquits himself well, and several of the foreign diplomats write respectable reports about the new Danish monarch.

In the 18th century, Denmark was an autocratic monarchy. The country is deeply dependent on the monarch making sound decisions, but it quickly dawns on the officials surrounding Christian that the new monarch is not capable of leading the country. They scheme against the king and manipulate him. Christian reacts with wildness, and soon he spends more time ravaging the streets of Copenhagen with his mistress Støvlet-Cathrine and a gang of young friends than he does leading the country. They regularly get into fights with the night watchmen, the police at the time, and at home at Christiansborg, Christian shows off the morning stars he takes off the watchmen.

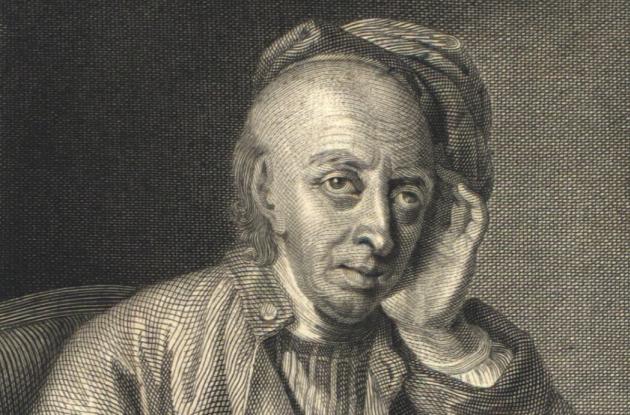

In his study, Bolle Willum Luxdorph sits and takes notes in his diary. On the table is a book with Luxdorph's seal, an elephant with a crown in its trunk. He gives marks to all the books he reads. Some get the fine distinction of "placuit", others, like this one, get the predicate "dirt". Luxdorph loves books, and he is a collector with a capital C. At the time of his death, Luxdorph had collected more than 15,000 books. Many of them we now have at Det Kgl. Bibliotek. We know this because they are marked with Luxdorph's elephant.

Bolle Willum Luxdorph's well-developed collector's gene is central to our history, but let's return to King Christian for a moment. Like many other rich and noble people of the day, Christian wants to go on a Grand Tour in Europe. He is to visit a number of European courts and with him, he has a large entourage, including a young doctor named Johann Friedrich Struensee. The doctor is strongly preoccupied with contemporary Enlightenment ideals, and he and the king develop a remarkable relationship during the journey. The officials around the young king quickly notice Struensee's positive effect on the king. Christian VII behaves better and there is a longer interval between embarrassing scenes at the foreign courts.

In 1769, the king returns to Copenhagen, and Struensee is hired at court. The ambitious doctor quickly gains more power over the easily influenced king. He begins to forge ties with the queen, Caroline Mathilde, resulting in the highly famous and fateful affair between the two. Eventually, Struensee outmanoeuvres the other courtiers and officials, and by the end of 1770, Struensee is the country's de facto regent. He introduces reform after reform to make the somewhat old-fashioned kingdom more modern. He is inspired by the Enlightenment ideals of freedom and greater equality.

In this storm of intrigue, Bolle Willum Luxdorph moves relatively unnoticed. He is part of the civil service and is most concerned with looking after his work and his books. But one of Struensee's reforms captures the attention of the history-conscious and book-loving Luxdorph. On 14 September, 1770, Struensee introduces freedom of the press in Denmark. Now everyone can write and print what he or she wants, even anonymously. There are no rules for what you can write, and the Danish freedom of the press is the most unlimited in all of Europe. Thanks to the freedom of the press, there is an overflow of pamphlets and writings sold in the streets and in Copenhagen pubs. Luxdorph realises that it is a breakthrough and he begins to gather the writings. The writings are about everything between heaven and earth, and just as we use social media today to have an informal conversation, 18th century Danes used the freedom of the press to have their say. One could say that the writings became the Facebook of the time.

For Struensee, freedom of the press will be the beginning of the end. He dreams that the Danes will contribute new thoughts and grand, noble texts, but in reality, there is a torrent of writers who are more interested in insulting others, fantasizing about powerful conspiracies, or writing derogatory texts about priests and Jews, than they are in enlightened debates. And what is worse, more and more of the writings begin to revolve around Struensee's reign and close relationship with the Queen. The public mood is turning on Struensee, and even though he tries to rein in the writings with new legislation, he does not succeed.

Struensee's power fades, and in January 1772, he is arrested. After a trial in which Struensee is probably subjected to torture, he admits his relationship with Queen Caroline Mathilde, and on April 28, 1772, he is taken to Øster Fælled. Here awaits a large crowd and the executioner with his axe. First Struensee's hand is cut off, and then he is supposed to be beheaded, but Struensee twists in pain and the executioner misses his mark. The executioner chops once more, but only on the third try does he manage to separate Struensee's head from the body. This marks the end of freedom of the press, which slowly disappears under the new regime.

Fortunately, Bolle Willum Luxdorph has collected the many writings and bound them in 47 volumes. They give an invaluable insight into 18th century Denmark. That is why he is our hero. Maybe he is one of yours now too? We have digitised all the writings with support from the Carlsberg Foundation, and you can read them online in Danish and find the past's opinions on greedy grain buyers, sailors and easy-going women.

Freedom of the press writings

Dive into the many writings from the time when censorship was abolished.