Christmas of the poor

Christmas is characterised by abundance, yet poverty takes up a fair share of our stories about the Christmas season. We have been in the collections and have found some of the Christmas stories.

Copious amounts of roast pork and duck, browned potatoes, rice porridge, all kinds of spicy home-baked goods and candle-lit Christmas trees, under which lies a blanket of Christmas presents wrapped in shiny paper and red bows. Christmas is, in many ways, a cornucopia and a veritable feast of consumption, yet poverty appears in many of our stories about Christmas.

Photo: Christian Emil Rosenstand

According to Caroline Nyvang, who is a senior researcher at Royal Danish Library, poverty has long been a large part of our society, especially during the holidays. All the way back to the older farming communities, there has been a common awareness in most of the world that one should provide for those who did not have much - not only at Christmas, but also at other holidays.

Traditions such as going from door to door and "begging" for money and sweets, which we know from Mardi Gras and Halloween, also stem from the idea that you should take care of those who do not have much. This may also be the reason why poverty has crept into our Christmas stories.

The contrasts of Christmas

A Christmas classic that the vast majority of people know - albeit in different versions - is Charles Dickens' A Christmas Carol from 1843. In the Christmas tale, the miserly and grumpy businessman Ebenezer Scrooge believes that Christmas is pure "humbug", and he tries to make the sweet Christmas time unbearable for everyone. Particularly for his shamefully underpaid employee Bob Cratchit, whom Scrooge barely wants to let off on Christmas Eve.

On the night of Christmas Day, Scrooge is visited by three ghosts – one from the past, one from the present and one from the future – who give him something to think about. One of the visits takes him to Bob Cratchit and his family's house, where the poverty is palpable and their youngest son, Tiny Tim, is terminally ill, but they cannot afford the proper treatment to make him well. Still, they celebrate Christmas Eve with a modest Christmas dinner, where the kind-hearted Bob Cratchit even raises a toast for Scrooge, even though he is in many ways the reason the family lives in such dire straits. After the three visits from the ghosts, Scrooge wakes up a changed man on Christmas Day, determined to make amends for his years of miserliness, mistakes and bitterness.

Dickens' Christmas adventure is set in one of the 19th-century cities, where industrialisation and urbanisation had created prosperity for the few, but poverty, hunger and hardship for the majority. In the Christmas tale, you really encounter the contrasts in society, and phenomena such as the debtors' prison, the slums and child mortality, which all refer back to the development of society, where many, especially the workers, lived in poor conditions. Especially at Christmas time, the contrasts in society became clear. The wealthy could celebrate the Christmas season with abundance, while the poor had to make do.

Photo: H. C. Andersen

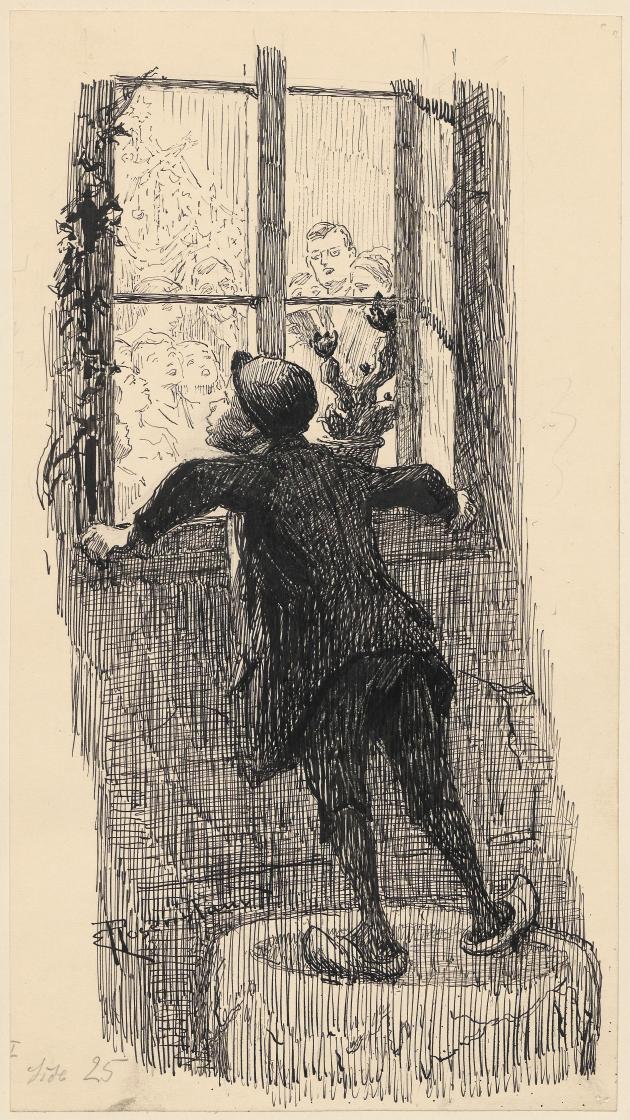

Christmas on the other side of the window

Another classic that you are guaranteed to know and which shows the contrasts of society is Hans Christian Andersen's heartbreaking fairy tale The Little Match Girl. On a cold New Year's Eve, while the snow is falling, a little girl is out selling matches so that she can earn a penny or two for her family. Light pours in from all the windows onto the street, and the smell of roast goose hangs in the air.

To keep warm, the little girl rubs a stick of sulphur along the wall of the house, and in the glow of the little flame the girl sees a hot tiled stove. For each of the matches she lights, the glow of the flames provides a new scenario; a china-covered table with a steaming roast goose filled with prunes and apples, a green Christmas tree with thousands of candles, and finally, as she swipes the rest of the bundle of matches at once, the girl's grandmother appears.

The girl begs her grandmother to take her with her. The next morning, passers-by find the little girl frozen to death. Although the tale ends tragically, the little girl has a smile on her face because she has ended up where she wanted to be. At her grandmother's.

Also in Sophus Schandorph's poem The Poor Boy's Christmas Eve from 1863, a poor, frostbitten and homeless boy must look enviously through the windows of families who, with bellies full of roast goose, dance around candlelit Christmas trees.

While other Toddlers celebrate Christmas

all in the cosy living Room,

dance happily under green Trees

by variegated Voxlight's Flame,

the poor Boy, has tears on his cheeks,

to the Windows long he gazes,

he breathes in small numb Hands,

of cold his Body trembles.- Sophus Schandorph, The Poor Boy's Christmas Eve, 1863.

Christmas for the Christmasless

Although poverty plays a part in our stories about Christmas, this does not mean that Christmas has only been reserved for the wealthy part of the population. On 24 December 1910, Anker Kirkeby, a journalist for Politiken, went into the darkest part of Copenhagen. More precisely, he went towards the Brøndstræde quarter. The neighbourhood behind the Round Tower and towards Gothersgade in Copenhagen, where poverty, crime and prostitution prevailed at this time. Here he searched for traces of Christmas among the city's homeless - but he found no traces of the sweet Yuletide.

He found drunken Men, he found Women covered in thin Shawls frozen by the Wind, he found small Children crying from Hunger, but not any traces of Christmas until he reached Holger Danske Sailors' Inn in Prinsensgade. Here was sweet Punch and free apple slices (...)

Two days later, on Boxing Day 1910, Kirkeby's description of the Christmas night walk was printed in Politiken, but what few knew was that Kirkeby would be inspired and give Christmas back to the Christmasless, as he called them.

Already the following year, the first Christmas party for the Christmasless was set up with the help of the town's more well-to-do citizens. The Odd Fellows Mansion in Copenhagen provided magnificent premises for the celebrations, where a Christmas dinner consisting of traditional rice porridge and Christmas beer, meatballs with potatoes, and cake and coffee was served, and each guest received a Christmas present. It could contain a few useful little things, a warm sweater, a warm scarf or a pair of woollen mittens and perhaps a small memento such as a Christmas book or a toy, so that the guests could retain a piece of the Christmas spirit when the lights on the Christmas tree burned out. Both the gifts and the Christmas dinner were donated by the town's citizens, traders and manufacturers in the food industry.

Photo: Holger Damgaard

In addition to the Christmas dinner, the Christmas party also offered entertainment. The Royal Life Guards' Music Corps played well-known Christmas tunes, and the Danish actor and writer Elith Reumert (1855-1934) read Hans Christian Andersen's Christmas fairy tale The Little Match Girl aloud for the guests. It is believed that around 2000 people turned up for the first Christmas party in 1911. Kirkeby had created a tradition which was repeated year after year.

The standard of the Christmas party reflected the ups and downs of society. In the years following the first Christmas party, support increased, and the Christmas dinner that was served resembled a traditional Christmas dinner more, with the meatballs replaced by roast pork. During the occupation, Denmark's decline could be felt, and it was difficult to obtain food, goods and gifts. Still, they were able to open the doors to the Odd Fellows Mansion on Christmas Eve.

The Christmas of the Christmasless became an annual event from 1911 until Christmas 1970.