The other half

Ever since Jacob Riis photographed the poor of New York in the 1890s, photography has been used for documentary depictions of environments unfamiliar to the average citizen.

Showing how the other half lives

How well should you know the people you are photographing?

Documentary photographers often focus on portraying other and less privileged social groups than those to which they and their audiences belong.

Some spend years with the people they portray, becoming part of their communities. Others use an outsider position to render visible things that may not be clearly seen from the inside.

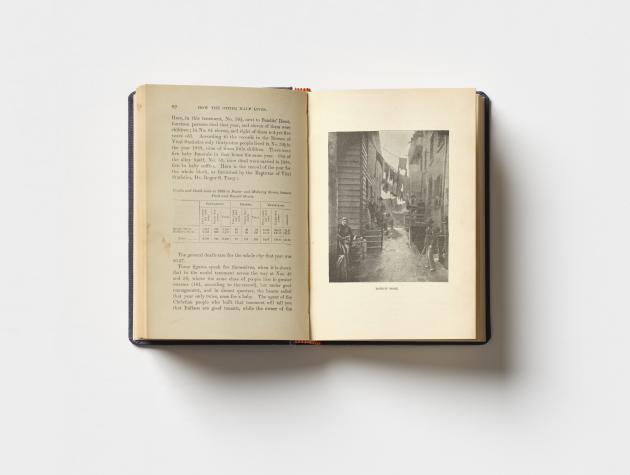

From photography book to reform

Danish-born Jacob Riis was a social reformist, reporter and photographer who created the 1890 book How the Other Half Lives, one of the first examples of photojournalism. Lit by the harsh light of flashes, Riis captured the darkest, dankest backyards of New York, revealing the miserable living conditions of the city’s poorest residents. The book’s images are infused by a certain sensationalism, yet also reflect a desire to create change. It succeeded in doing so: the book had great political impact and helped prompt reforms and improvements to housing conditions.

Photo: Anders Sune Berg

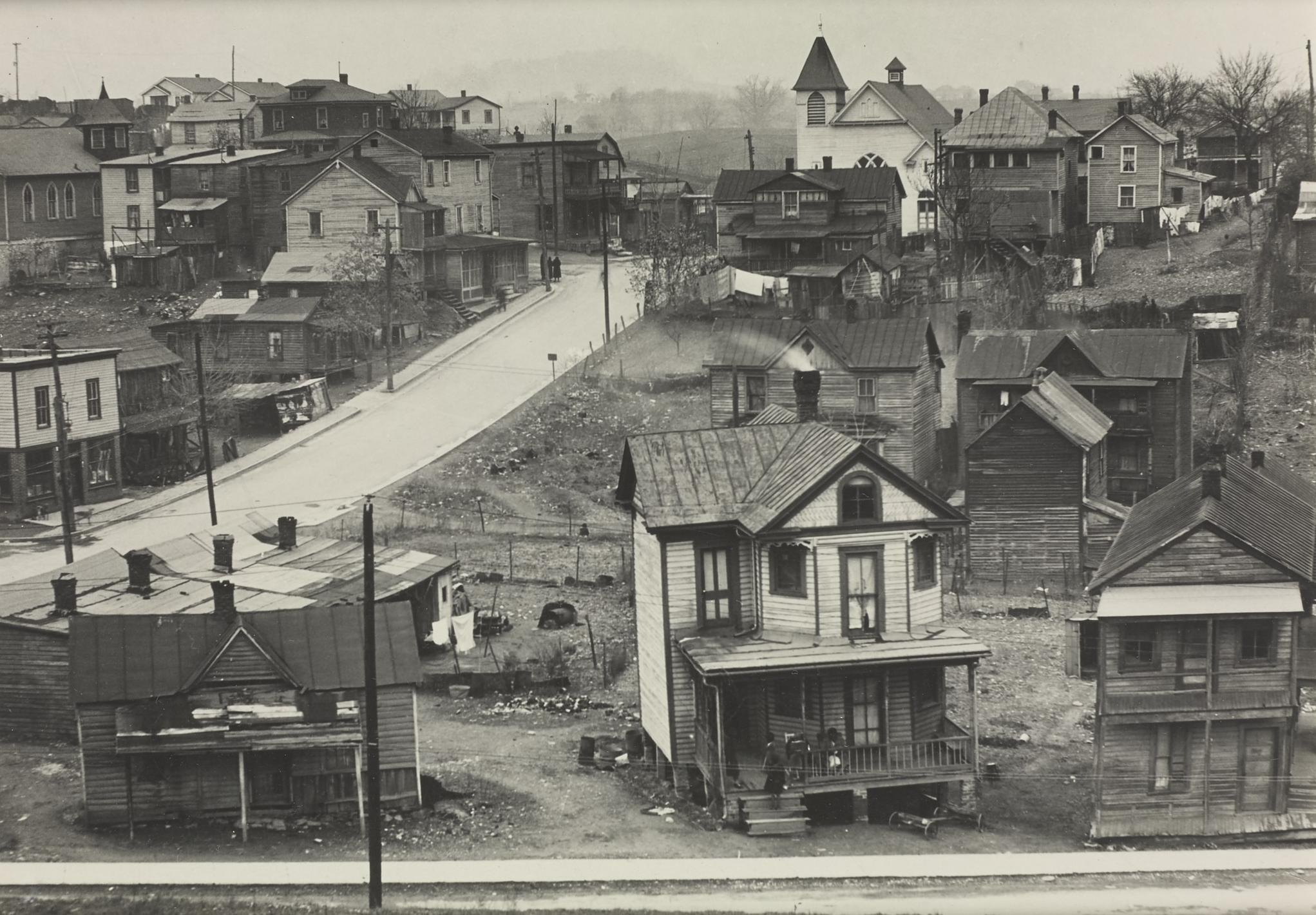

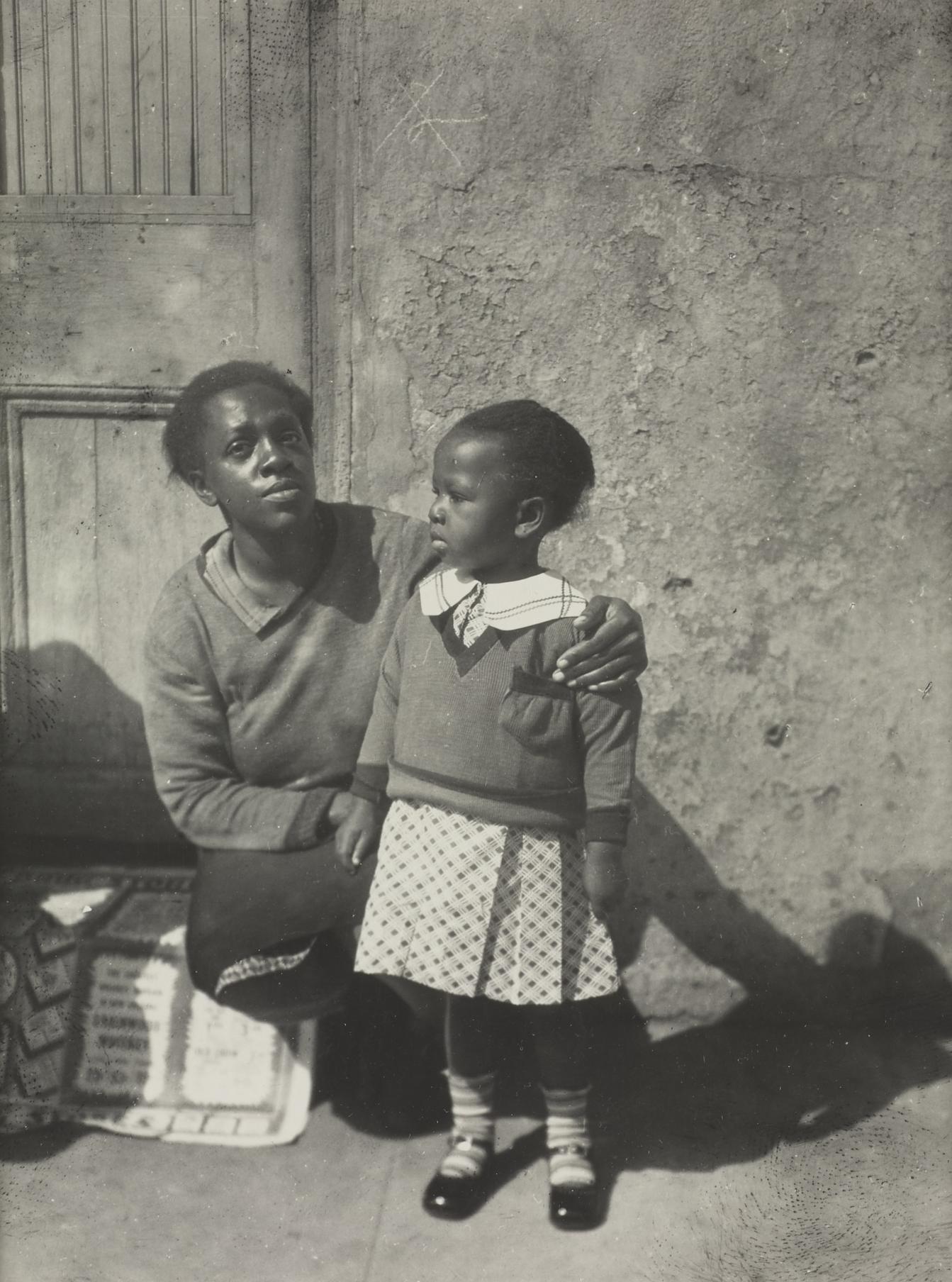

Peter Sekaer

Peter Sekaer set out from Denmark to the United States in 1918 and became a photographer in the 1930s. He took pictures during the Great Depression, a time when unemployment and poverty were widespread. Among other things, he assisted Walker Evans on several trips around the country. Having arrived in America from a society that was in many ways very different, he had a keen eye for distinctly American traits. This was especially true of racial segregation and the massive discrimination and oppression found in the South.

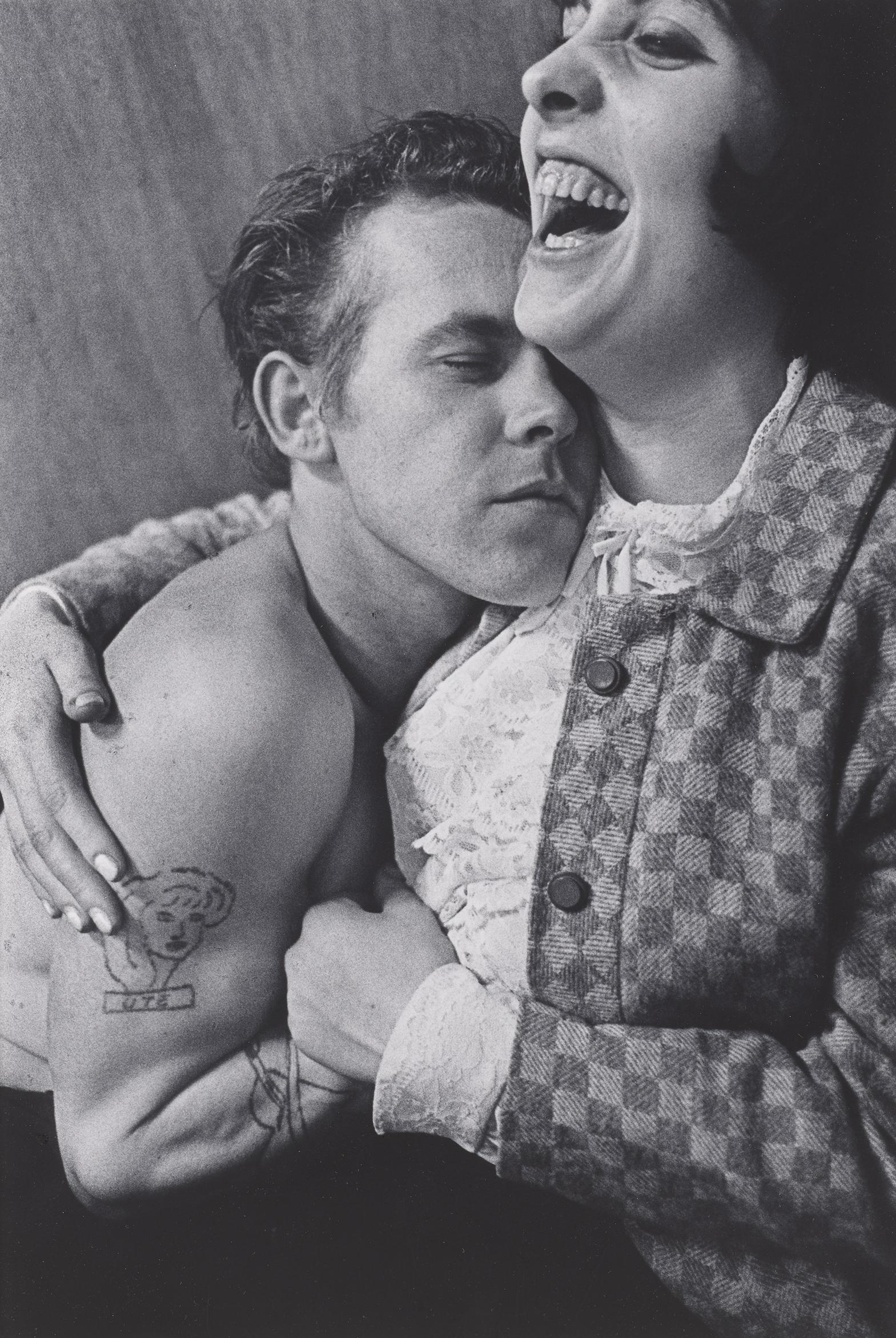

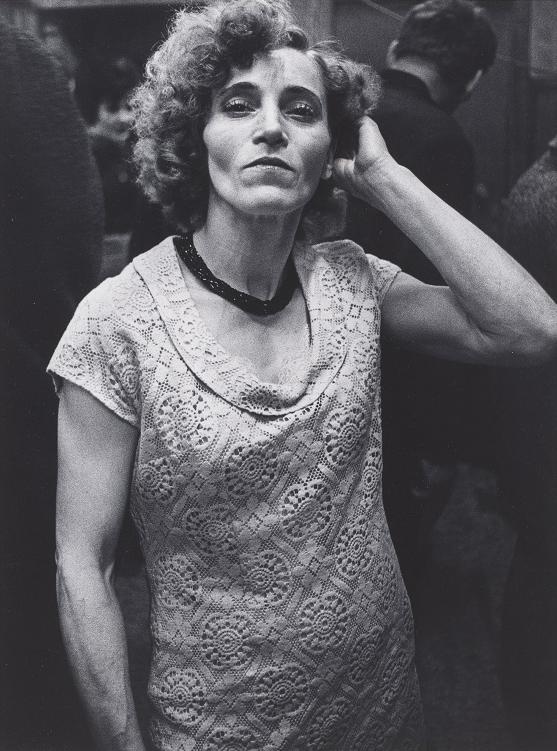

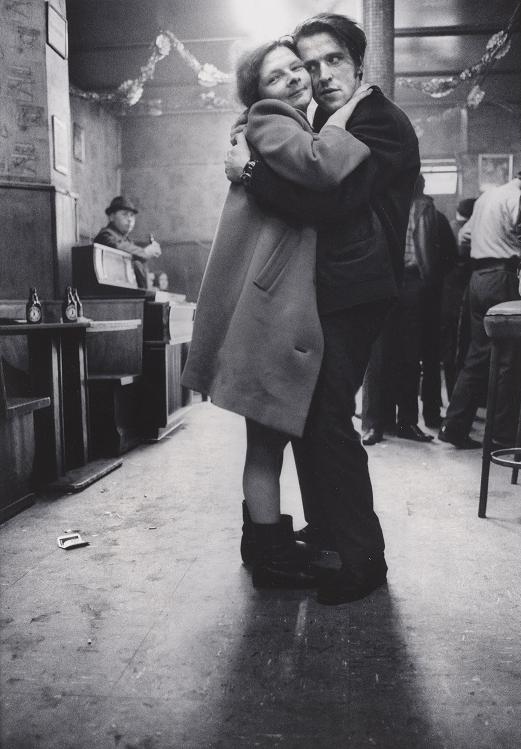

Anders Petersen

For two and a half years, Swedish photographer Anders Petersen regularly visited a bar in the red-light district of Hamburg. Here he took pictures of the regulars, who mostly lived on the outskirts of society and worked locally. He established a close rapport with the clientele, depicting their sense of community, the flirtation, the fights, the fun. You only get something out of your subjects if you give something back, says Anders Petersen, and there is a clear sense of trust and confidentiality in the pictures – even as you might also feel that the characters are being put on show.

Martin Parr

Martin Parr photographed life on New Brighton beach in Liverpool in the eighties, a time when the British economy was at its lowest ebb. In Parr’s pictures, we see how people from the impoverished working class flock to a run-down beach to enjoy life in each other’s company despite all adversity. Parr’s use of saturated colours and flash photography highlights the litter and decay. Do we sense a certain distance to a lifestyle that the photographer is slightly mocking? Or is this simply a picture of a country in a state of disarray and dissolution?

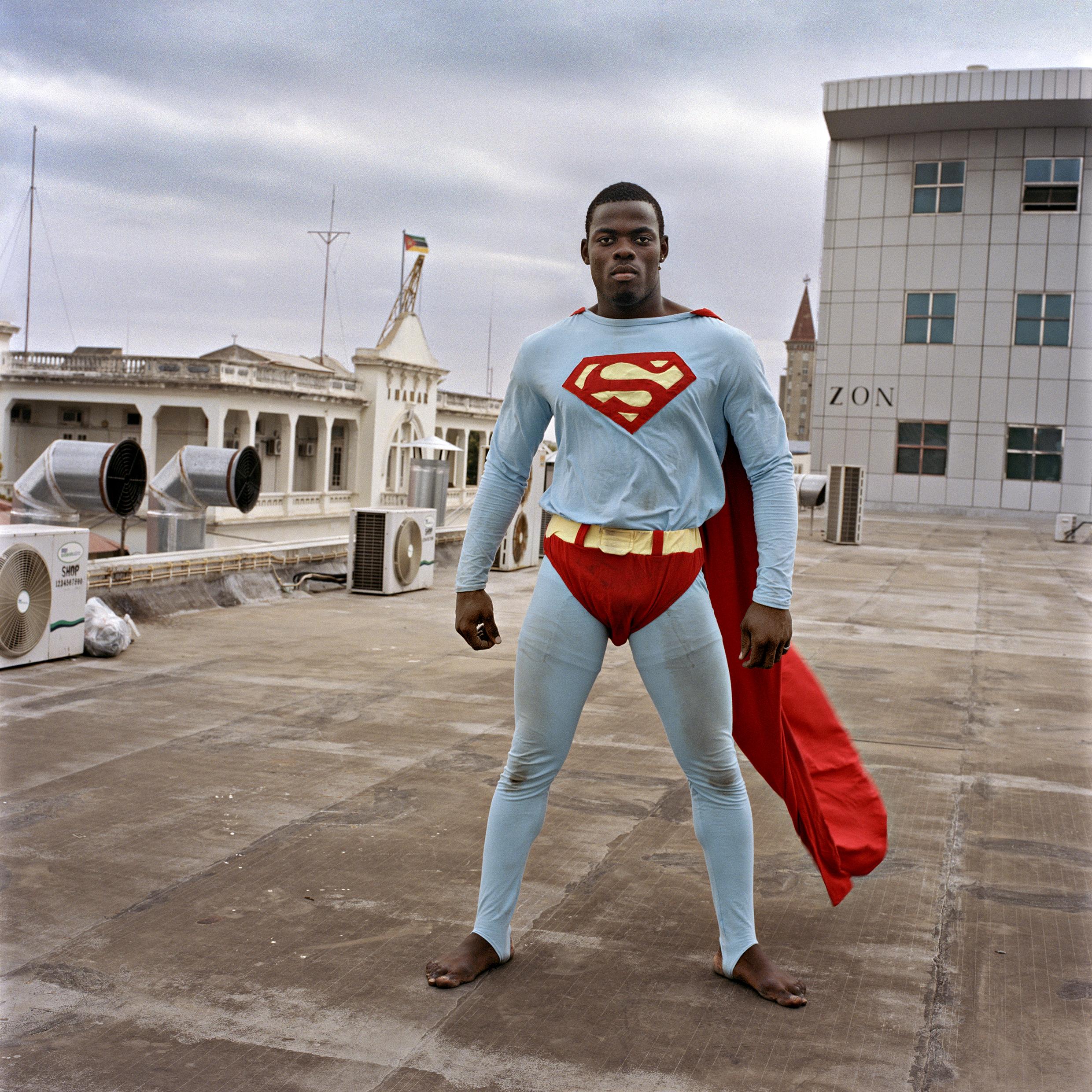

Ditte Haarløv Johnsen

Ditte Haarløv Johnsen grew up in Maputo, capital of Mozambique. As a white Dane in the African city she was an outsider, one who got on well with other outsiders. She later returned as a photographer, documenting her circle of acquaintances, friends, family and lovers. Many of Ditte’s friends were homosexuals and transgender people who had been expelled from home and had to make a living from prostitution as well as live with AIDS. With her series, she wanted to express solidarity, vitality and unity.