The 1926 election - The first live broadcast election meeting

The 1926 election was the first election to be broadcast by radio. We delve into the election campaign of the time and the first live broadcast voter meeting.

The roar from Idrætshuset

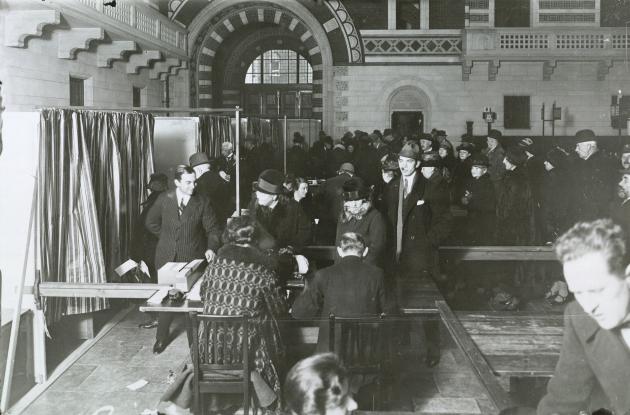

You would almost think there was a national match. Despite the frost and snow, thousands and thousands of people stood in the area outside the Idrætshuset in Copenhagen. They looked up towards the balcony, where a couple of loudspeakers had been placed so that everyone could follow what was happening inside the house.

Inside, the great hall was full of people. Those from the upper-classes were sitting, most were standing, while the most agile had climbed up the stall bars. On the hall floor stood a lectern at one end. Here the four politicians from the largest parties stepped forward in turn to deliver their election speeches.

Photo: Holger Damgaard

The first was former Minister of Agriculture Thomas Madsen-Mygdal from Venstre, the Liberal Party of Denmark. He only had time to open his mouth before a storm of angry shouts erupted from the audience. They were primarily social democrats. However, he got his main message across: That taxation on wealth was a mistake, and that public spending should be significantly cut instead.

The next man on the scaffold was Vilhelm Rasmussen from the Social Democrats. He was on home soil, but mostly talked about the politics of the others. Because it was the others' fault that there were now elections, and that meant you could not move forward with solving the crisis instead. Big round of applause and on to the Conservatives' man, Drachmann. His speech was also partially drowned in boos. The same happened to the last speaker, Danish Social Liberal Party's Dr P. Munch, that is, apart from when he praised the Social Democratic government, and so it continued throughout the evening.

At one point the moderator interrupted the speakers to inform them that at this moment, he had received a telegram from Svendborg with a request from the listeners for quiet for the speakers, as they otherwise could not hear anything

. The request helped only a little, and in the following days it was precisely the noise from the audience that was incomparably the big topic of conversation in the press.

Social bubbles and fair media

If you read the various newspaper reports from the 1926 election, it is very clear that social bubbles and echo chambers are not a new thing. Long before the Internet and social media, people lived in very different worlds depending on which newspaper they read. According to the blue press, the election meeting was a definite scandal because of the behaviour of the Social Democrats. According to the red press, the meeting was extremely successful. There was a bit of a fuss. But a skilled and competent orator quickly got a handle on it.

What the truth was is always a little hard to dig into without the primary source, but it tips heavily to the blue side. Thus Horsens Avis, whose report was based solely on the radio transmission, described how the sound from the meeting itself was really good, but that it was sometimes impossible to hear what was said due to the noise from the audience.

For instance, nothing the chosen Conservative voter said was quoted, simply because the reporter could only hear the boos. He only managed to call the Social Democratic female minister Nina Bang the ministry's enfant terrible

, before he was brutally shut down by the red hordes on the rafters.

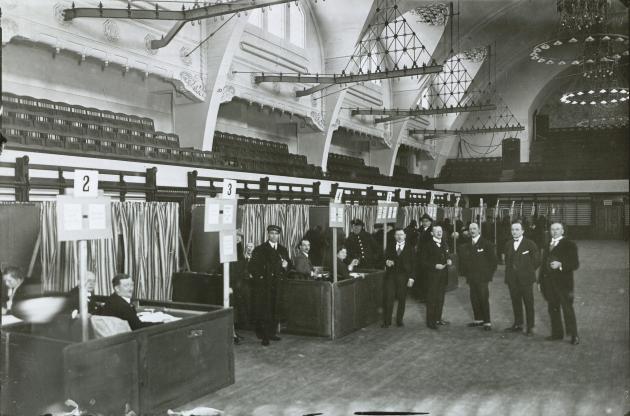

Photo: Holger Damgaard

It had probably always been like this at these kinds of meetings, but it was the first time that you could hear it with your own ears, regardless of where you were in the country. Until the breakthrough of the radio, you only had the reports of the newspapers to rely on, and then it was a question of who you believed the most.

Now you had a completely different basis on which to make your choice. And that was the very basic idea of the State Broadcasting Corporation. That all perspectives in the Danish population came to be spoken in turn, and that all citizens thus had an insight into each other's world. It was the original meaning of public service and a beautiful democratic thought. Which was of course very difficult to unfold in practice.

To that extent, it was an excellent meeting, which Venstre has every reason to be satisfied with. In return, isn't there a feeling of shame within certain social democratic circles?

New media – new content

The first live broadcast election meeting in 1926 may not have been the most successful of its kind. At least not from a social democratic perspective, because the bad behaviour was the absolute main talking point afterwards. On top of that, Venstre was so on the ball that they simply placed an ad in a number of newspapers with the headline Was the roar from Idrætshuset not thought-provoking?

. The message was clear and distinct, that everyone now knew what a wild and undemocratic group you belonged to if you voted Social Democrats. And that this was obviously how Copenhageners behaved.

But it was new territory, from both the radio's side and the political side.

The live transmission of the voters gave the impression that you were present yourself. Although from the birth of the radio, people were extremely attentive to public voices when they were recorded in the studio, no one had foreseen what would happen when you record an election meeting. They other live transmissions outside the radio studio in 1926 were from church, where there is a fixed dramaturgy

, says the research librarian at Royal Danish Library Anna Lawaetz, who has, among other things, researched voices.

Photo: Holger Damgaard

The speaker of the evening probably had the listeners' ears in mind, but the other participants were clearly not yet that aware of the new media's rules of the game. For the Danish listeners, the broadcast was a censorious hell of noise when opponents of the Social Democrats tried to say something. The fact that they said the same thing as always was secondary. The new media required new ways of saying things, and both as a party and as a politician you had to think in a completely different new way about how you spoke and behaved when you were "on".

Politicians' awareness of the voice as a carrier of authenticity gradually grew with the radio medium. In relation to politicians' voices and the ideals attached to voices, one could perhaps imagine in the future a showdown with the idea of the powerful voice. For our unconscious aesthetic ideals of the good radio voice and the good political voice are dynamic. What gave the ethos in 1926 for a politician in terms of voice is certainly not the same today. We will not be addressed by a patriarchal, lecturing voice, but the politician must rather take the role of the knowledgeable friend we can respond to

, says Anna Lawaetz.

Today, almost 100 years later, the premises are completely different. As a politician, you must be on a selection of different digital platforms, preferably all the time, and be able to master many different genres. And as a voter, it is perfectly possible to follow everything. And when the election month is over, there have been so many televised and webcast election meetings that few can remember what was said at the first one. And maybe that is not where we are now at all. Perhaps it is the Tiktok format of very short videos that will be a deciding factor. In any case, today's politicians can take some comfort in the fact that tough talk and sneaky attempts to shut down the other party are certainly not a new invention.

Photo: Dagens Nyheder

Why was there an election in 1926?

The election in 1926 was held two years after the first Social Democratic government had taken office in 1924. The government lacked a majority in Parliament and had to seek a compromise.

The result of the election was that Venstre and the Conservative People's Party won a majority. Stauning and his government therefore had to resign, and on 14 December 1926 Venstre's new leader, Thomas Madsen-Mygdal, was able to present the new blue government.