UKRAINIAN DIARY – Photograph of Boris Mikhailov from 1966 to today

Experience this year's big photo exhibition in The Black Diamond with one of Eastern Europe's most influential photographers.

Review

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

...a current and poignant exhibition, which can sometimes seem harsh, but which also contains poignant photos characterised by great humanism [...] It is not to be missed!...

- Cultural information

Photo: © Boris Mikhailov, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

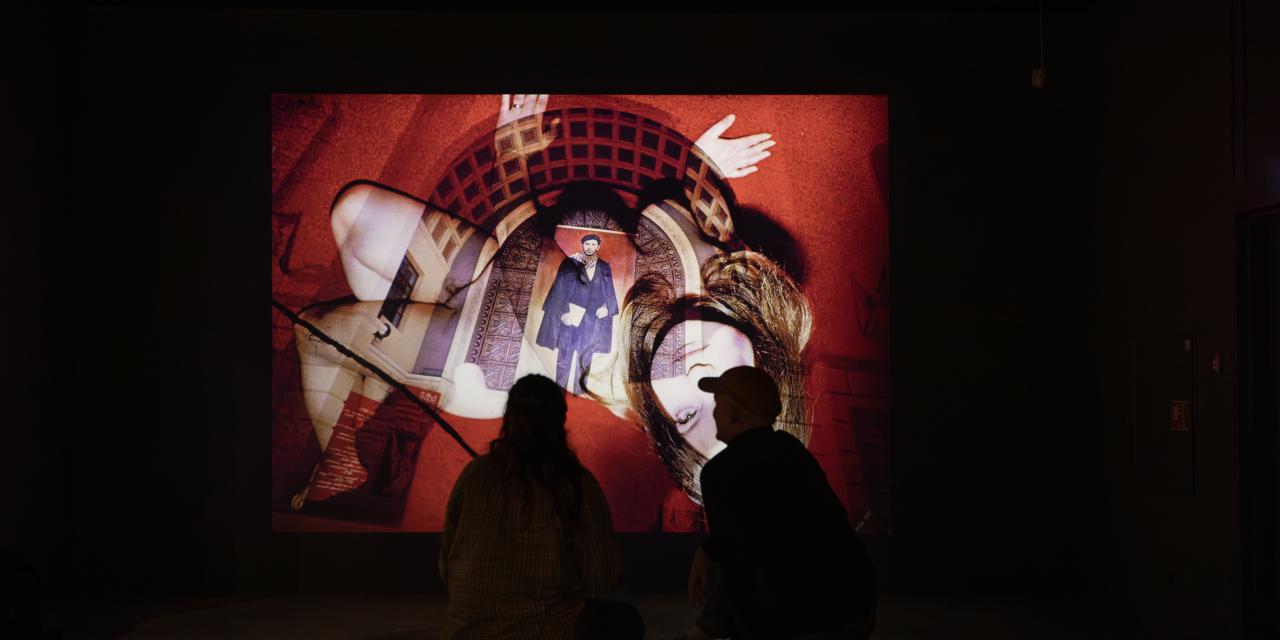

Ukrainian Boris Mikhailov is one of Eastern Europe's most influential photographers, who has documented life in his homeland for half a century. The result is a poetic, beautiful, harsh, ugly and frightening contemporary look into life before, during and after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Now you can experience his award-winning art in The Black Diamond.

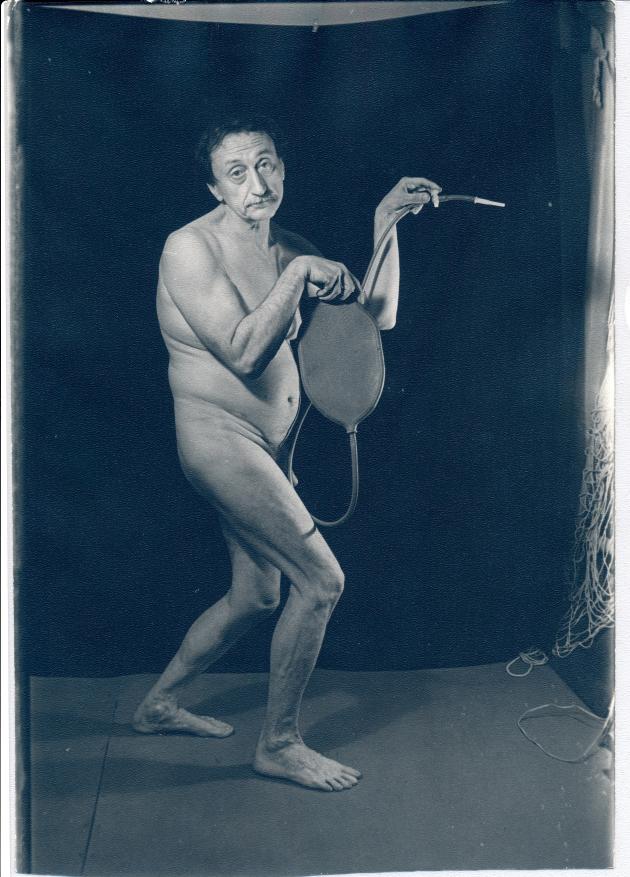

Ukrainian Diary is the first retrospective exhibition of Boris Mikhailov in Denmark. With over 500 works, the exhibition is not just a merciless look into Ukraine's tumultuous history over more than half a century. It also presents an artist's impressive life's work, spanning vastly different artistic methods and aesthetic expressions. His works range from humour to tragedy, from social realism to the pop; from documentation of the total poverty and destitution that prevailed in Ukraine under the Soviet Union to almost burlesque nude pictures of the artist himself.

From rebel to revolutionary

Boris Mikhailov's photography career began after the KGB fired him from the factory where he worked as an engineer in the 1960s. Here he had secretly used the state-owned factory's camera and darkroom to take and develop nude photos of his then wife. A motive that in Soviet-ruled Ukraine was deeply illegal.

Now unemployed, he devoted himself to photography full time. A risky venture, as under the communist rule you were only allowed to take "authorised" photos that confirmed the Soviet regime's glossy image of society.

Mikhailov and his friends also began to secretly organize small anti-system exhibitions in their homes, so-called "dissident kitchens". This group of photographers later formed the nucleus of the Kharkiv School of Photography – one of the most influential artistic movements of the Soviet era, known for its experimental approach to photography and its often provocative and conceptual style.

About Boris Mikhailov

Photo: Vita Mikhailov

Boris Mikhailov's uncompromising and merciless visual language has made him one of the most important artists in contemporary photography. He has influenced generations with his critique of Soviet society and raw exposition of themes such as everyday life, sexuality, the body, despair, poverty and mortality.

Mikhailov has received many prestigious awards and his work has been shown in numerous solo exhibitions around the world, including Tate Modern, London (2010), MoMA, New York (2011) and at The Ukrainian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, (2007).

Boris Mikhailov lives and works with his wife Vita in Kharkiv and Berlin.

Louisiana Channel

Hear Boris Mikhailov talk about his life and his art in this interview that the Louisiana Channel did with him when Mikhailov visited Denmark in connection with the exhibition opening.

Thank you to

The exhibition is supported by Handelsgartner Harry Opstrup's Foundation and the Politiken Foundation and organised in collaboration with MEP - Maison Européenne de la Photographie, Paris.

Curator: Laurie Hurwitz in collaboration with Boris and Vita Mikhailov

Curator for Royal Danish Library: Charlotte Præstegaard Schwartz