Halloween

Creepy costumes, pumpkin lanterns and Halloween decorations have become a permanent tradition in many Danish families on 31 October. We shed some light on the long history of Halloween.

Like with so many other recent traditions, we have seemingly imported the celebration of Halloween straight from the United States. But where does the tradition really come from? Halloween originally has its roots in much older history and consists of elements from both Christianity as well as ancient northern European beliefs.

Read on as we go back to the old Irish tales of evil spirits and a man named Jack who has to travel between heaven and hell with a very special turnip lantern.

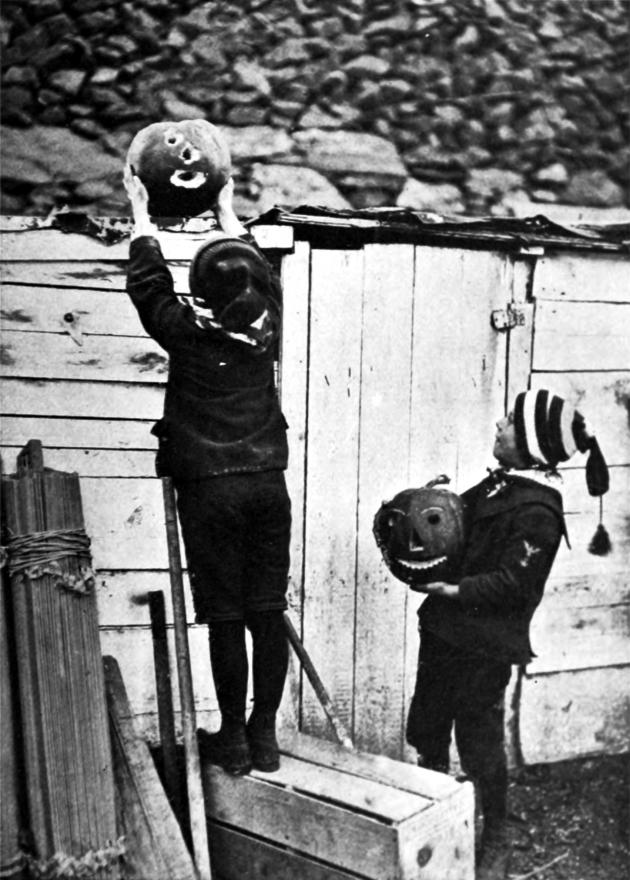

Photo: Wikimedia

The pagan Halloween

We find the first celebrations of what would later become Halloween very far back in history, namely in Irish folklore.

The pre-Christian Celts of Ireland celebrated a great feast called Samhain, which lasted several days in early November. Samhain was both a celebration of finishing the harvest and a celebration of the end of summer and the beginning of winter.

The Celts believed that those who had died during the year travelled to the realm of the dead under Samhain. The dead were thus particularly active these days and moved like spirits among the living. The light from a bonfire helped keep the evil spirits of the past away, which is why fire was an important part of the original tradition.

When the Celtic territories became Christian around the year 500, the church took over the holiday. Now the day was to remind the people of all the Christian martyrs and saints. Gone were the tales of witches, trolls and evil spirits.

The day was no longer allowed its pagan name, Samhain. Instead, the day should have a Christian name, that being 'All Hallow Even'. It eventually became the more idiomatic word we know today: Halloween.

Photo: Wikimedia

Across the Atlantic and back again

In the mid-19th century, thousands of Irish people fled to America due to the famine. Both the Irish and the Scots brought their traditions with them, including Halloween.

Since then, the custom spread and further developed, so that today it is one of the biggest holidays in the United States. Through newspaper articles, television and books, the tradition spread across the Atlantic once again, but in a new form. Now the evening is celebrated almost like a carnival with terrifying costumes, spooky door decorations, fireworks and trick and treating.

As we in the Western world have moved further and further away from the Christian traditions, the pagan origins of Halloween have been allowed to re-enter the tradition. Now witches, ghosts and all sorts of creepy costumes are haunting the streets for Halloween again. The children go from house to house in their neighbourhood and threaten "trick or treat!"

Although the American celebration of Halloween may seem far from the Samhain of the Celts, there are still some clear recurrences. We find this in the contrast between darkness and light, among other things. Even though we no longer light bonfires, light in the form of pumpkin lanterns are still an important part of the tradition,

says Caroline Nyvang, senior researcher at Royal Danish Library's folklore archives.

But why do we hollow out and carve scary faces into innocent pumpkins for Halloween these days?

Photo: Book of Halloween/Wikimedia

Why do we carve pumpkins for Halloween?

In Denmark, carved pumpkin lanterns on the doorstep have become a regular sight around Halloween within the last 20 years. But the tradition is actually much older than that. There are records from the last 100 years from various Danish regions, where it is reported that a turnip lantern with an eerie face is placed somewhere it could scare others.

In England, Scotland and Ireland, there has long been a tradition of hollowing out different kinds of beets and using them as lanterns. In 1837, the term "Jack-O-Lantern" was first seen used about a lantern carved in a vegetable - not in the British Isles, but in America. It is also in the United States that the combination of Halloween and a hollowed out pumpkin appears in 1866.

Yet many associate the luminous pumpkin head with Ireland. This is due to the Irish legend that tells of Jack, a lazy and cursing drunkard of a farmer. There are different versions of the legend, but in all versions Jack succeeds in fooling the Devil himself. They make a deal that the Devil must not tempt Jack or demand his soul.

When Jack dies, he, with his non-pious way of life, cannot enter Heaven. Since he has fooled the Devil himself, he cannot enter the gates of Hell either. Instead, he receives from the Devil a small piece of glowing coal, which can light the way for him on his journey back to Earth. In order for the glowing piece of coal to last as long as possible, Jack puts it into a turnip, and with the light from the lantern, he now wanders restlessly in the darkness between Heaven and Hell.

Old traditions in new clothes

Just 20 years ago, many predicted that Halloween would not have a long life in Denmark.

At the time, the thought was that a new tradition like Halloween was a commercial invention. An excuse for the stores to sell more. The Danish business world has surely been very instrumental in bringing Halloween within the country's borders, but it takes more than a few good bargains for a new tradition to take root among us.

Today, Halloween is one of the most popular ways to face the darkness of winter. The tradition has become especially popular among the younger population, which is why Halloween has become a permanent tradition in most families with children and in primary schools.

The elements of faith and seriousness that existed in ancient times have disappeared. The seriousness has been replaced by good-natured jokes and horror gimmicks. The old traditions stemming from northern European folk beliefs and Christianity have thus taken new shapes in the form of spooky costumes, scary pumpkin heads and orange candy and decorations.

Photo: Line Beck

I begyndelsen af 90'erne, da efteråret satte ind, rapporterede danske aviser om en særlig fejring, der tiltrak opmærksomhed fra både børn og voksne rundt omkring i landet. Det drejede sig om en fest, der kom helt fra Amerika. Græskar fik mærkelige ansigter, og folk klædte sig ud i farverige kostumer. Det var halloween, der stille og roligt begyndte at finde sin plads i danskernes hjerter.

““Græskarene var i centrum, da en flok danske børn i går fejrede Halloween, den amerikanske allehelgensaften. På restaurant Newport i Hellerup morede de udklædte børn sig bl.a. med at skære i græskar, så de forvandledes til græskerhoveder.

Photo: Det Kgl. Bibliotek

Men højtiden var stadig fremmed et stykke tid endnu. Hvert år, når slutningen af oktober nærmede sig, rapporterede aviser om hekse, spøgelser og vampyrer på gaden og spindelvæv i alle hjørner på den anden side af Atlanten. Det kunne for udlændinge godt være en uhyggelig oplevelse, at stifte bekendtskab med det amerikanske samfund i oktober måned.

Det var først hen mod slutningen af årtiet, at halloween tog rigtig fat herhjemme. Som mange andre nyere traditioner og fejringer, blev højtiden importeret via den amerikanske popkultur. Men halloween har oprindeligt sin rod i en meget ældre historie og består af elementer fra både kristendommen såvel som gamle nordeuropæiske trosforestillinger.

Photo: Keld Helmer-Petersen (1920-2013)

En hedensk begyndelse

De første fejringer af det, der senere skulle blive til halloween, finder vi meget længere tilbage i historien, og slet ikke i Amerika - nemlig i den irske folketro.

De før-kristne keltere i Irland fejrede en stor fest kaldet Samhain, der varede flere dag i begyndelsen af november. Samhain var både en fejring af, at høsten var i hus og en markering af sommerens slutning og vinterens begyndelse.

Kelterne troede, at dem, der var døde i løbet af året, rejste til de dødes rige under Samhain. De døde var altså særligt aktive i disse dage og færdedes som ånder blandt de levende. Lyset fra et bål var med til at holde fortidens onde ånder væk, hvorfor ild var vigtig del af den oprindelige tradition.

Photo: Keld Helmer-Petersen (1920-2013)

Da Irland blev kristnet omkring år 500, overtog kirken helligdagen. Den skulle i stedet minde befolkningen om alle de kristne martyrer og helgener. Langt væk var fortællingerne om hekse, trolde og onde ånder.

Mærkedagen måtte ikke længere have det hedenske navn Samhain. I stedet fik dagen det kristne navn allehelgensaften eller 'All Hallow’s Eve'. Det blev med tiden til det noget mere mundrette ”halloween”.

Over Atlanten og tilbage igen

I midten af 1800-tallet flygtede omkring to millioner irere til Amerika på grund af hungersnød. De medbragte deres traditioner, herunder halloween.

Siden bredte og udviklede skikken sig. I dag er den en af de helt store festdage i USA. I dag fejres aftenen nærmest som et karneval med udklædning i skrækindjagende kostumer, uhyggelige dørdekorationer, fyrværkeri og drillerier. Og det er altså den amerikanske version, som siden har spredt sig til Danmark og mange andre lande.

Nu løber små hekse, spøgelser og alskens uhyggelige uhyrer i gaderne i slutningen af oktober. Børnene går fra hus til hus i deres nabolag og truer med ”slik eller ballade!" Men kan man finde rester af den irske fejring af overgangen mellem sommer og vinter i den moderne halloween?

““Selvom den amerikanske fejring af halloween kan virke langt fra kelternes Samhain, er der stadig nogle klare gengangere. Det finder vi blandt andet i kontrasten mellem mørke og lys. Selvom vi ikke længere tænder bål, er lys i form af græskarlygter stadig en vigtig del af traditionen.

Photo: Keld Helmer-Petersen (1920-2013)

Hvorfor skærer vi græskar til halloween?

I Danmark er udskårne græskarlygter på dørtrinet blevet et normalt syn op til halloween. Men traditionen er faktisk meget ældre end som så. Der findes optegnelser fra de seneste 100 år fra forskellige danske egne, hvor der berettes om at stille en roelygte med et uhyggeligt ansigt et sted, hvor den kunne skræmme andre.

I såvel England, Skotland og Irland har man længe haft tradition for at udhule forskellige slags roer og bruge dem som lanterner. I 1837 ses for første gang begrebet ”Jack-O’Lantern” om en lanterne udskåret i en grøntsag – ikke på de britiske øer, men i Amerika. Det er også i USA, at kombinationen af halloween og et udhulet græskar dukker op i 1866.

Alligevel forbinder mange det lysende græskarhoved med Irland. Det skyldes det irske sagn, der fortæller om Jack, en doven og bandende drukkenbolt af en bonde. Der findes forskellige udgaver af sagnet, men i alle udgaver lykkes det Jack at narre selveste Djævelen. De indgår en aftale om, at Djævelen ikke må kræve Jacks sjæl, når han dør.

Photo: Det Kgl. Bibliotek

Da Jack stiller træskoene, kan han med sin ufromme livsførelse ikke blive lukket ind i himlen. Men på grund af hans pagt med Djævlen, kan han heller ikke lukkes ind bag helvedes porte. I stedet må han vandre på jorden. Djævlen giver ham et lille stykke gloende kul, som kan lyse for ham på hans færd. For at det glødende kulstykke skal holde så længe som muligt, lægger Jack det ind i en roe, og med lyset derfra vandrer han nu hvileløst i mørket mellem himmel og helvede.

Gamle traditioner i nye klæder

For blot 20 år siden spåede mange, at halloween ikke ville få en lang levetid i Danmark.

På det tidspunkt var opfattelsen, at en ny tradition som halloween var et kommercielt påfund - en undskyldning for, at forretningerne kunne sælge mere. Den danske handelsstand har da også været medvirkende til, at det er blevet så populært at fejre halloween i Danmark. Men der skal mere til, for at en ny tradition finder rodfæste blandt os. Vi skal have lyst, overskud og råd til den, og vi skal kunne bruge en ny skik til noget. Ellers bliver den aldrig så populær, at den kan overleve på lang sigt.

Halloween falder på en årstid, hvor der ikke er mange fastforankrede danske helligdage eller traditioner at konkurrere med. Oven i købet er Danmark placeret på en breddegrad, hvor man netop mærker kontrasten mellem sommerens lyse nætter og vinterens mørke stærkt. Her passer halloween måske meget godt ind.

Photo: Line Beck

How do we know this?

The folklore archives in Royal Danish Library stores several hundred years of documentation of people's daily lives in Denmark. We have large collections of recollections, fairy tales and legends as well as documentation of traditions and folk culture from all over the country. The archive's researchers and archivists work with everyday culture. In the past, people in particular were interested in the country's culture, but today the culture of all population groups is of interest, and our employees work with both historical and contemporary conditions. Unlike the museums, we focus especially on oral and written narratives and traditions.