Knud Rasmussen's great sledge journey

In 1923, Knud Rasmussen set off on the last big leg of the 5th Thule Expedition from Canada to Siberia. We have been in the collections to follow in Knud Rasmussen's sledge tracks.

From the summer of 1921 until the early spring of 1923, Knud Rasmussen and the rest of the members of the 5th Thule Expedition had the same base.

Photo: Peter Freuchen

In Hudson Bay on a small island they had named Danish Island, they had built the base Blæsebælgen. From here they set out on longer and shorter expeditions around Hudson Bay, and they always returned. In a logbook, they kept careful records of who left, where and when. On 11 March 1923, just over two years after the start of the expedition, there is just a line next to Knud Rasmussen's name. The line indicates that Knud Rasmussen left on this day with no intention of returning to Blæsebælgen.

From Hudson Bay to Siberia

The arctic spring was ahead of them, and Knud Rasmussen set off together with the Inuits Arnarulunguak and Qaavigarsuak on the last, big trip of the expedition, often called The great sledge journey. The journey would take them several thousand kilometres from Hudson Bay, along the coast of Arctic Canada and the northernmost coast of Alaska to the northeastern corner of Siberia. The final destination was the East Cape. The sledge was light, and the load consisted only of provisions for the first days and some of the lightest and most desirable trade goods, such as sewing needles, knives and pearls, which they might need to trade with on the journey.

Who was Knud Rasmussen?

Knud Rasmussen was a Danish polar researcher and anthropologist and the son of the Danish missionary Christian Rasmussen and Sofie Lovise Susanne Fleicher, whose mother was Inuit. He was born and lived the first 12 years of his life in Ilulissat, Greenland. Beginning in childhood, Knud Rasmussen had a great interest in the origins and culture of the Arctic people, and he often went exploring in Greenland researcher Hinrich Rinks' books about the Inuit in his father's library.

In 1912, Knud Rasmussen, together with journalist, writer and explorer Peter Freuchen, started the first of a total of seven Thule expeditions, of which the fifth became the largest and most significant expedition. The expedition was to investigate where the Inuit originated and how their culture had developed in the diverse geographical areas from Canada to Alaska.

The willow branch

After 17 days in deserted areas, they encountered the first people on their way up to Pelly Bay. During a raging snowstorm, while they were repairing their snow hut, two well-grown men appeared in the snow-covered landscape. Meeting strangers was always a serious matter for the Inuit. You never knew whether it was friends or enemies you met on your way.

Photo: Ukendt ophav

Nevertheless, Knud Rasmussen met them tenaciously and unarmed, and fortunately they arrived in peace. The men were the father, Orpingalik, the one with the Willow Branch, and his son Kanajoq, Sculpin, who were on their way to Repulse Bay to sell their 75 or so fox skins so they could buy some new guns. Knud Rasmussen and his companions decided to brave the blizzard and follow the one with the Willow Branch and his son back to their campsite.

We met as if we had known each other for a long time, and a reunion with old friends could not have been more cordial. Frozen salmon and reindeer meat were laid out for us, and while we ate and enjoyed ourselves together with the women in the warmth of the house, the men immediately set about building a large, spacious snow hut

The meeting with The One with the Willow Branch turned out to be unusually interesting. He was a respected spirit mage, a good hunter and archer, the fastest of all in a kayak and wise in the ancient traditions of his tribe. Together with him, Knud Rasmussen managed to get about 100 legends and rare spells written down.

This meeting was just the first of many hundreds of meetings with Inuit on the journey. In an area near the Boothia peninsula and the magnetic north pole, Knud Rasmussen met the Netsilik tribe, who still lived a Stone Age life where they hunted with bow and arrow, lit fires by drilling wood against wood and built snow huts with bone knives. Soon after, Knud Rasmussen met the five-year-old Tertâq, or Amulet Boy, as Knud Rasmussen called him. He got the nickname because he wore over 80 amulets in his leather anorak, which were sewn into the inner and outer fur of the anorak. Each amulet had a spiritual purpose, such as the raven, which was supposed to give him a good overview when hunting, and seaweed, which was supposed to make him a skilled kayaker. Knud Rasmussen changed into the Amulet Boy's leather anorak, and it is today on display at the National Museum in Copenhagen.

In the fall of 1923, they reached Alaska, where they encountered tribes that were very different from the tribes they had previously encountered. Until now, they had lived among Inuit who lived by catching game on land and who only hunted marine animals caught from the solid ice. The tribes they met now spoke a language that was very reminiscent of Greenlandic, and they lived by catching game from the sea in kayaks and from boats. Moreover, sea animals were not the only thing they hunted. Here, too, gold and money were in high demand, and the Inuit showed signs that they had been in contact with civilization.

At the end of the sledge track

Photo: Ukendt ophav

In the farthest corner of Siberia to the east lived the westernmost of all the Inuit, and here the expedition was to end. In September 1924, Knud Rasmussen reached Alaska's westernmost point, and to reach his final destination he had to cross the Bering Strait – the narrow body of water that separates Russia from Alaska. Here one storm succeeded another, and the natives only sailed their skin boats if the wind came from a certain direction. The other alternative was to sail with a schooner, a larger boat, with several white men like Knud Rasmussen on board. Landing in the East Cape with others like himself would arouse the distrust of the native tribes - but the journey had to be made. However, that was not his biggest problem. Knud Rasmussen did not have his entry papers in order, and after much negotiation with the Soviet police chief in the East Cape, he had to sail back to Alaska the following day. When he was back on land again, a telegram from the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs awaited him. It contained the residence permit for the East Cape.

Fate can be so capricious. The telegram came exactly one and a half months late

The expedition's findings

Photo: Det Kgl. Bibliotek

Despite the fact that the expedition did not end as Knud Rasmussen had wanted, the benefit of the journey was great. During the three years the expedition had lasted, they had collected more than 20,000 objects, which were brought home to Denmark and donated to Danish museums.

After the journey, Knud Rasmussen was able to prove that Inuit from Greenland, Canada, Alaska and Siberia, despite different ways of life, lifestyle and primary prey, were all connected through language, mythology and common stories. Their common origins could be traced back hundreds and even thousands of years. In addition, the expedition resulted in a number of books, a thousand photographs and a film. Among other things, in 1925-26 he published his own account of the great sledge journey in the two-volume work From Greenland to the Pacific.

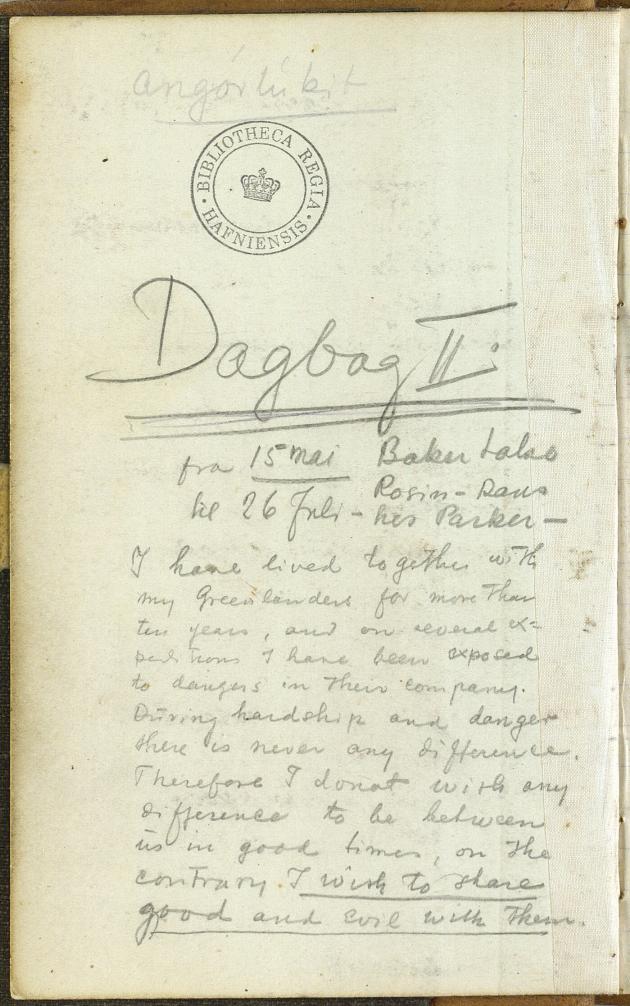

Dive into Knud Rasmussen's archive

In Digital Collections, you can explore pictures and Knud Rasmussen's diaries from the 5th Thule Expedition. You can also find 20 out of the 21 volumes of Ethnographic Records, where Knud Rasmussen mapped large parts of his findings on the Inuit lifestyle and culture and contributed his own illustrations and sketches.