Do you get fooled by Slooflirpa?

April fools is a fixed tradition in many Danish media outlets. We trace the banter back through the Danish newspapers in our collections.

Most people have fallen for an April Fool's joke at some point - whether it has been fabricated by one of our loved ones or by the country's media. The mischievous tradition has, however, changed over time from innocent banter to more socially critical parodies.

The traditional April Fools is about getting a chosen victim to "run April". That is, to be sent off on an aimless errand to see something that is not there, or to retrieve a fictitious item that does not exist, as when the master craftsman asked apprentices to retrieve a “left-handed screwdriver” or scouts were sent off after “smoke deflectors”.

Photo: Franz von Lenbach

False stories hidden in the morning paper

The media in particular have carried on the April Fools tradition. At the end of the 19th century, the Danish newspapers began to report on April Fools' Day in the international media. On 5 April 1883, Morgenbladet could inform their readers that an Italian newspaper carried the story of a tri-coloured comet that would appear on 1 April. This comet had disappeared on the orders of the influential German Chancellor Bismarck, who was at the height of his power in those years, the Italian newspaper reported. In 1899, Slagelse-Posten reported more prosaically that a German newspaper would henceforth be published on edible paper.

Before long, the Danish newspapers themselves started making up April Fools. It happened in connection with the newspapers going from the four-paper system, where they were associated with one of the four major political parties, to becoming the omnibus newspapers that we know today. Newspapers that are politically independent and focus on broad-based news journalism. This meant that the Danish newspapers came to look more like the international ones, and there was thus room for some lighthearted teasing on 1 April. And with the newspaper as mass media, you had the opportunity to fool not just one person - but many at once.

In the beginning, it was mainly the local newspapers that hid a false story among the newspaper's local content. The purpose was to lure the citizens into the streets and chase the false story. In 1951, Aalborg residents could read in Aalborg Amtstidende that a flying saucer had landed in the city centre that same morning, and in 1971 the readers of Holbæk Amts Venstreblad could read that a transport plane bound for Switzerland had lost one million kroner in notes, which were now flying around a local bog. Often the false story was accompanied by a manipulated press image that piqued readers' curiosity.

Do you have an April Fools' Day story?

The Folklore Archives at Royal Danish Library has since 1904 documented Danish traditions. The collections give a good insight into the media's April Fools' pranks, but we have little material that can tell us how we have tried to trick each other within the family and at workplaces and educational institutions over time.

If you would like to contribute your story, you can do so by clicking here.

April Fools in the national newspapers

In the last decades of the 20th century, the national newspapers also began to adopt April Fools' Day jokes - but here it was in a different guise. In the national newspapers, they did not create locally-rooted false stories to lure people to the city centre, lakes and marshes, but rather they fabricated April Fools' jokes to a greater extent, which drew inspiration from the political debate and the social problems of the time. In 1986, Berlingske Tidende carried an April Fools' joke that the iconic clock in Copenhagen's town hall was to be replaced with a digital version made in Japan. The story that a Japanese company now had access to install cheap technology at one of the city's most prestigious addresses was a direct extension of the new technological possibilities, both breathtaking and terrifying.

Where does April Fools' Day come from?

It is not exactly known where April Fools' Day originated. Researchers point in different directions. Some believe the tradition has its roots in the Catholic Church and France.

In 1582, Pope George XIII ordered a switch from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar. This meant, among other things, that New Year's Day would henceforth fall on 1 January, as we know it today, instead of on 1 April, as it had previously done. Some countries, including France, were defiant and held on to the old traditions. Therefore, supporters of the new calendar made fun of those who reluctantly stuck to the old traditions on the First of April.

Others believe that the tradition originates from India, where for millennia the Holi festival has been celebrated at the end of March. Here there has been a tradition of sending people out on fake errands, and if you fell for the ruse, you were called a Holi-fool.

Spring has, like the New Year, been considered a transitional period, which has given rise to pranks and friendly teasing. For the past 400 years, there has been a tradition in Western Europe of making spring pranks throughout the month of April. In the Nordic countries, 1 April and 1 May have been special prank days that started and ended the fools' month.

April Fools also began to adopt traits from the satire genre, where one both parodies and criticizes parts of society through made-up tongue-in-cheek stories. In 1987, Ekstra Bladet carried an April Fools' joke that a special tax would be introduced for the obese, and later in Information under the heading "Men are redundant", you could read that women could now be fertilised with the help of hormones extracted from boar semen. Both stories were based on real stories, which, with a humorous tone – and a safe distance – were taken to the extreme and problematised.

Danish companies followed suit

Companies also became aware of April Fools' Day in the 1990s. A well-planned April Fools' joke could generate relatively cheap publicity. The supermarket Netto was among the first Danish companies to seize the opportunity. On 1 April 1996, they announced in Berlingske Tidende that they had obtained municipal permission to build a shop inside the iconic Round Tower. The fear that one of Copenhagen's most important buildings should be decorated with Netto's yellow logo took over conversations at the Danes' dinner table and also achieved publicity for several days in a large number of Danish media.

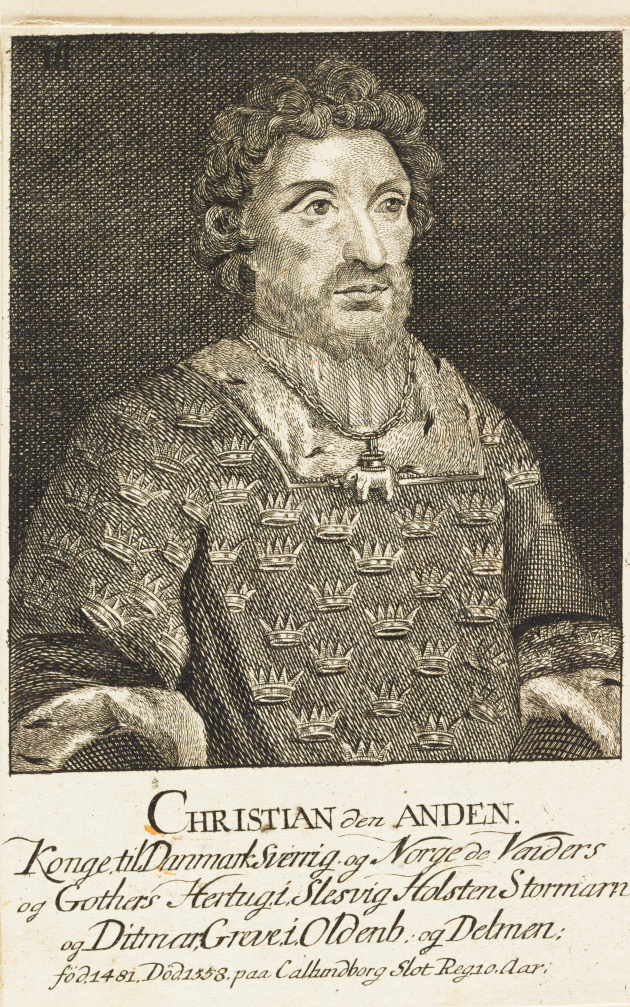

Photo: Ophav ukendt

"Taehc Bif" and "Slooflirpa"

Over time, several of the media's April Fools' Day jokes and pranks have been so close to reality that other media have reported on the stories – unaware that it was an April Fools' joke. It happened, for example, in 1928, when several Danish newspapers jumped on the story that the remains of Christian II's horsemen had been found in a Swedish prison cellar. However, journalists have in many cases tried to plant clues in the articles that the attentive reader would be able to find. For example, anagrams are often used there, such as Taehc Bif, which, when read backwards, says Fib Cheat and various variants of Slooflirpa - that is April Fools spelled backwards.

Is April Fools here to stay?

In a world where fake news is not reserved for 1 April, and where fake news permeates the media landscape, the tradition of April Fools in the Danish media has created debate. Several media, including Kristeligt Dagblad, have chosen to distance themselves from the tradition, while other media continue to stick to the mischievous tradition.

So there is still good reason to be critical when reading the news on the first day of April.