Family life caught on film

Family photo albums tell a story about the people they belong to, but also about how we generally use private photography to tell our intimate stories.

Cheek to cheek. We take a picture and become a couple. Ever since the birth of photography, the camera has been used to present a happy picture of family life.

In family albums dating all the way back to the 1860s, you can see how we have told the stories of our lives with pictures from everyday life and special occasions.

We still mainly share happy moments today, where the photo album has transitioned to social media and the camera is with us everywhere on mobile phones. By contrast, many artists work with the conflicts, breaks and losses that are also part of family life.

Royal Danish Library has a large collection of family albums. Some have been donated by affluent families wishing to make their family history part of the nation’s history. Others have entered the collection as part of the private archives of well-known personalities from the realm of culture. Yet others have been bought from secondhand bookshops or arrived as donations from estates after deceased people where no heirs wanted the albums. They all tell a story about the people to which they have belonged – and about how we use private photography to tell our own intimate stories.

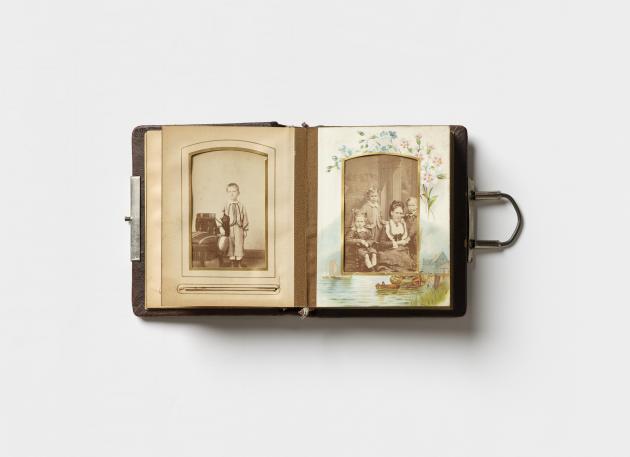

Carte de visite photos of the Willemoes family, ferrotype, albumen print etc., c. 1870

The Willemoes family album dates from the period when the nuclear family became an established format, with a working father and a stay-at-home mother. The family was not photographed in their own home, but in the photographer’s studio, which was made homelike by backdrops and furniture. The mother is presented as the unifying heart of the home. All are wearing their best, the pages are beautifully decorated, bound in leather, and a lock keeps these treasured moments of happy family life safe.

Photo: Anders Sune Berg

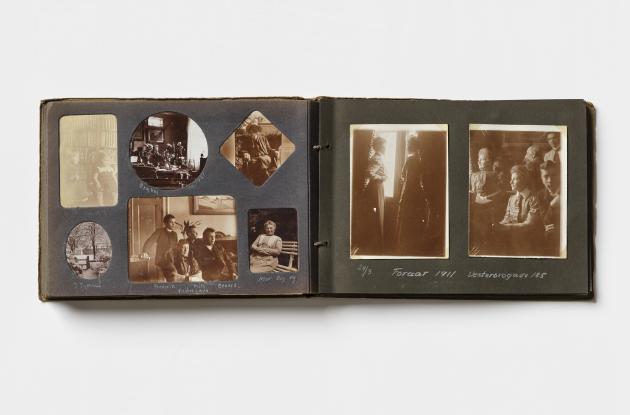

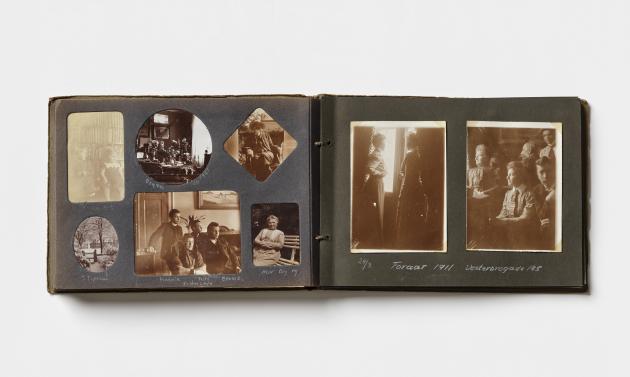

The Dahlberg family’s private album, c. 1890–1933

In 1888, Kodak launched its first camera for flexible roll film, meaning that you did not have to change film after every single photo. The number of amateur photographers increased dramatically in the following decades, and families now began to document their own lives with their own cameras. Many portraits were taken, but pictures from the home were also popular. In this case, the Dahlberg family called their album ‘Home’ and noted their successive addresses on the front cover.

Photo: Anders Sune Berg

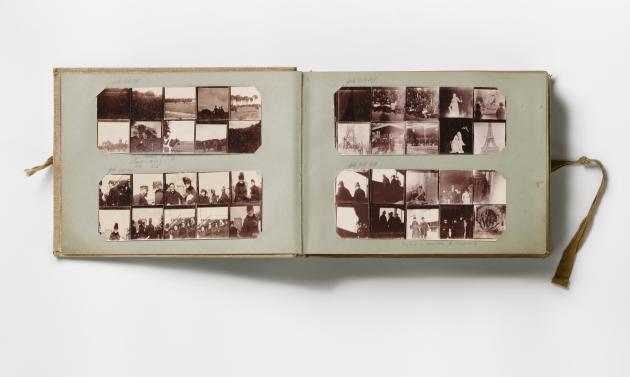

Private photos taken by the Kellermann family, gelatin silver print, c. 1897–1904

‘The first picture. 28/10 1897’ wrote doctor Asger Kellermann in neat handwriting on the first page of the album for which he took the pictures and wrote the texts. He directed his family to pose for group photos in their living rooms or garden, but also took the camera on excursions. Sometimes he made small tableaux of everyday situations and provided the images with titles.

Photo: Anders Sune Berg

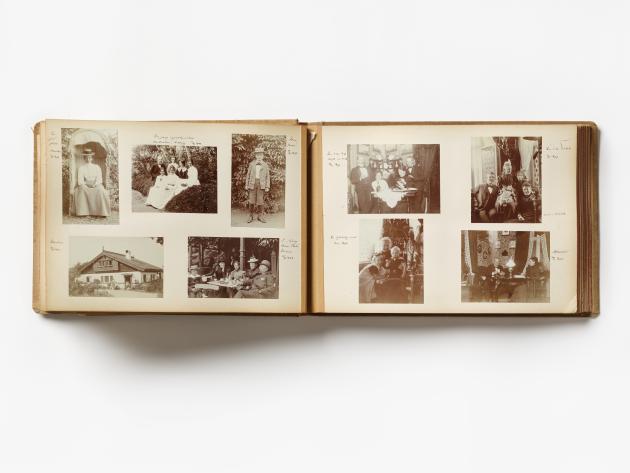

Private photos of the Hirschsprung family, collodion negatives and other techniques, c. 1900–10

The Hirschsprung family, known for their large art collection funded by the manufacture of cigars, continued the nineteenth-century tradition of taking posed pictures of family members. Here, in the early twentieth century, we see them posing by the garden table or inside at the piano. They also took more spontaneous pictures of scenes from everyday life.

Photo: Anders Sune Berg

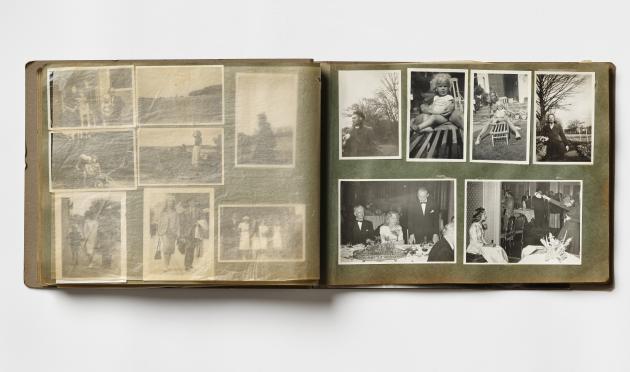

Tove Ditlevsen's private photos, gelatin silver print, c. 1955

Acclaimed Danish author Tove Ditlevsen’s album contains pictures of sunbathing and relaxed fun in holiday cottages and on trips abroad. Looking at the album today, the happy moments presented in this album form a counterpoint to the darkness we now know pervaded the author’s life at other times. In contrast to the press photographs in the album, the amateur photographs offer different and more private insights into her life – including the amateur photo showing her receiving a prestigious book award, viewed from one side with her eyes fixed on the press photographers’ flashlights.

Photo: Anders Sune Berg

Sune Amstrup

In Sune Amstrup’s series the subjects depicted are blurry and distorted. Faces and bodies appear strangely surreal in what otherwise looks like typical holiday and wedding photos. Some clear details can be discerned, but overall an algorithm has moved around the pixels in the photographs in a concrete embodiment of divorce and perhaps also of the pain of the memories involved. The family is no longer what it used to be, but even though everything

has become garbled, you still feel its presence lingering in the pictures.

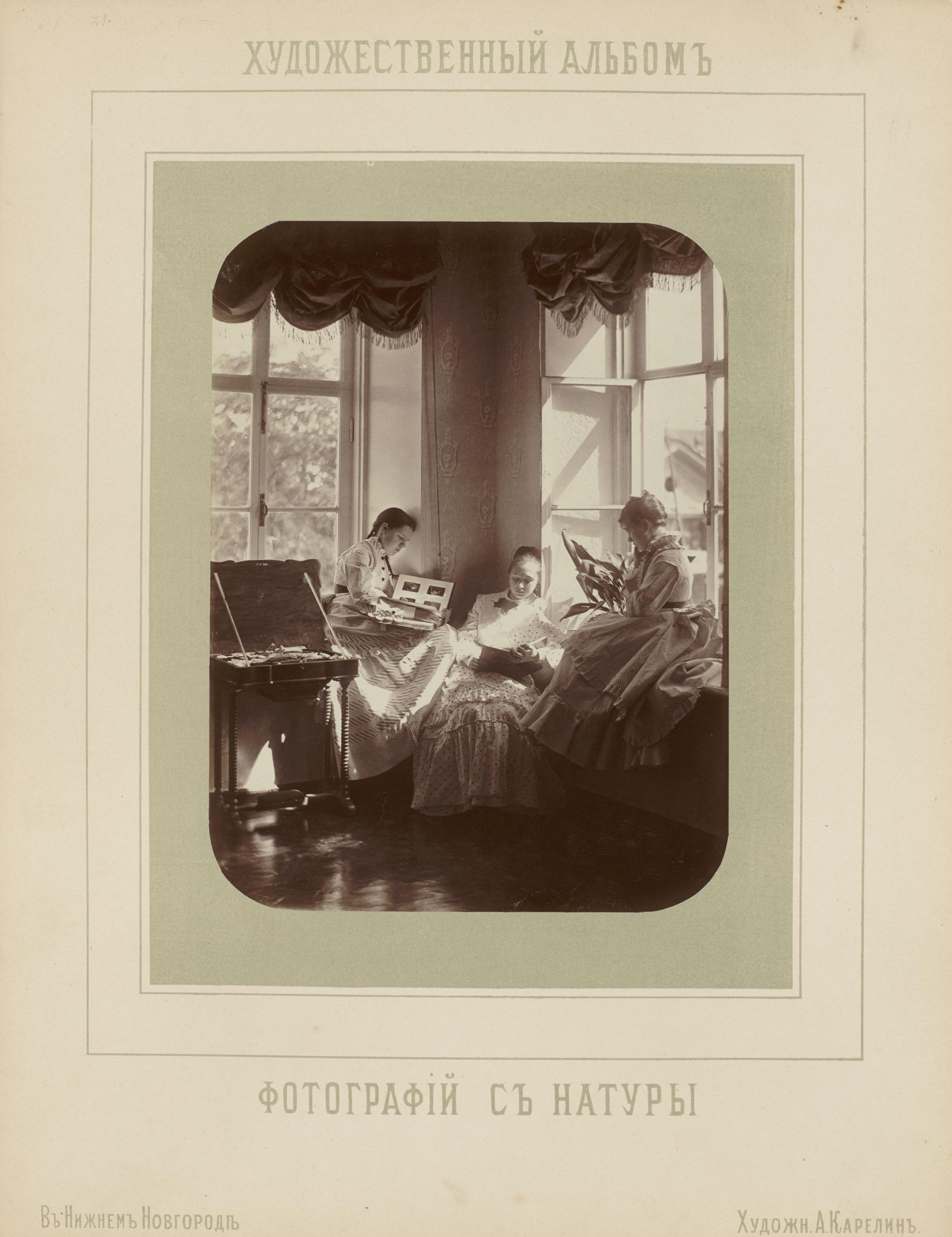

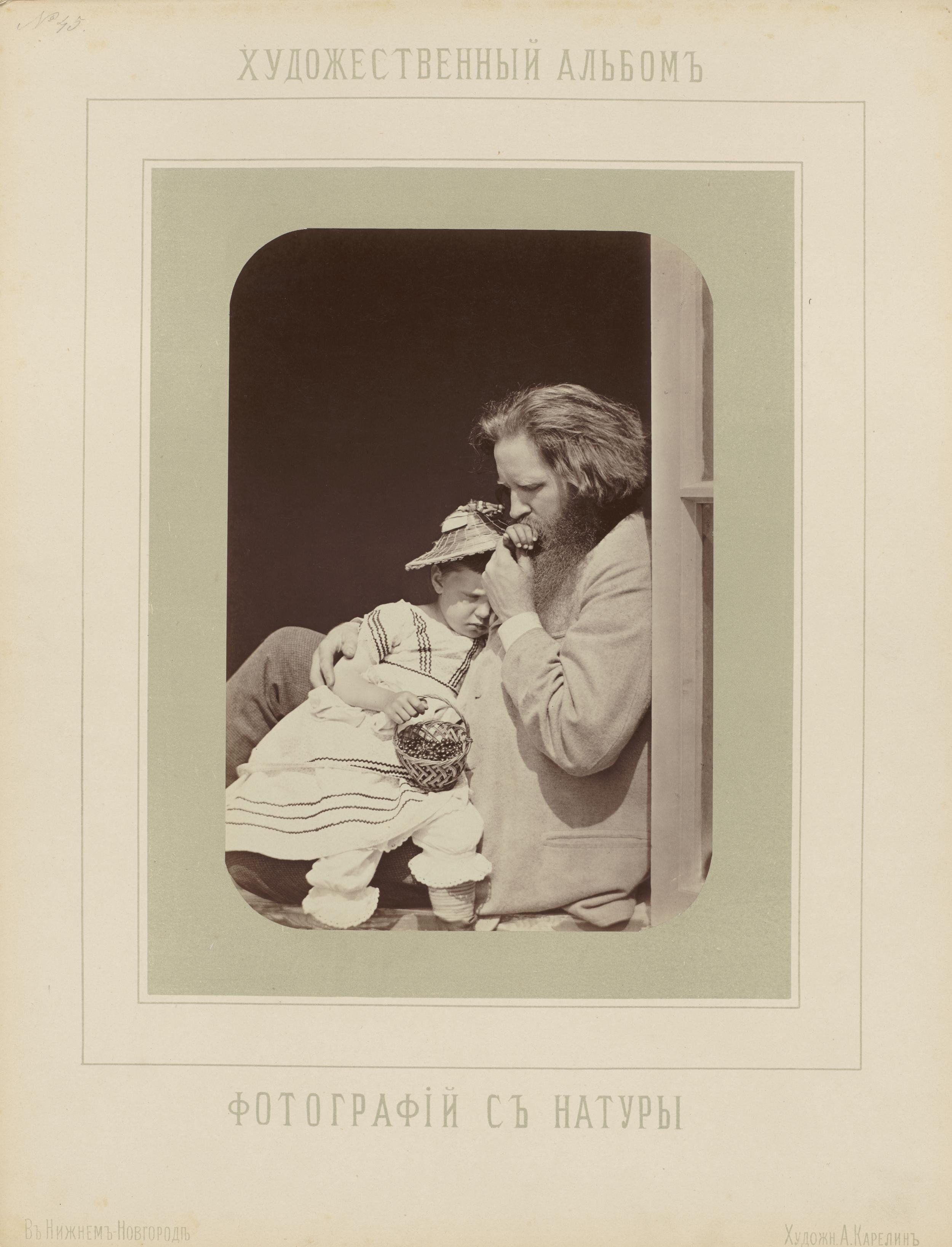

Andrej Osipovic Karelin

The Russian photographer Andrej Osipovic Karelin, who was a graduate from the Academy of Fine Arts in St. Petersburg, created family portraits inspired by Dutch Renaissance painters. Using his wife and children as models, he became famous for his detailed depictions of lighting conditions and soft furnishings. The images are like still lifes of his family, encapsulating the wider trend for depicting one’s family in a favourable light as well as photography’s ability to capture a vivid present which always, at the very moment it is taken, belongs to the past.

Stense Andrea Lind-Valdan

In her art, Stense Andrea Lind-Valdan works with the relationship between mother and son, between body and sexuality. Her photographs are reminiscent of the pictures we take in everyday life, and yet not at all. She often focuses on objects evocative of life and death, like a boiled egg or dead baby bird. Combining these with images of herself and her son, she places family life within a wider context of intimacy and transience.

Samira Nawa's Family Photos

MP Samira Nawa’s parents fled Afghanistan in 1986 and eventually settled in Aalborg, where they built a family. Nawa has no pictures from her grandparents, but quite a few from her own childhood. Even so, their number pales in comparison to the many pictures she has taken of her own family. Like so many others, she carries her phone with her everywhere and often uses it to take pictures of her family. She initially shared them on her private account on Facebook and Instagram, but she now also posts them on public profiles in her capacity as a politician.

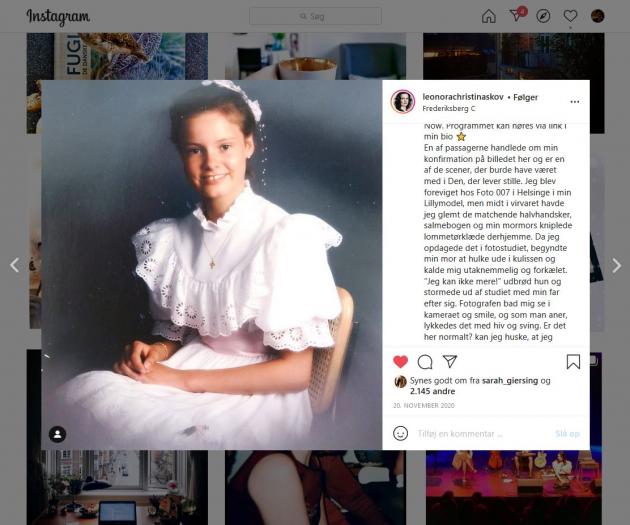

Leonora Christina Skov's confirmation photo on Instagram

Many point to the family photo album as the first thing they would rescue in the event of a fire. Conversely, photographs can also be something we want to get rid of if we do not like their content. Author Leonora Christina Skov, for example, has very few photographs from her childhood because her parents threw out their photo albums when she came out as lesbian. The confirmation photo was taken by Vagn Sangil in Helsinge in 1990.

Photo: Vagn Sangil