Communities

When the camera's lens captures us, it also captures what shows our sense of community. Many artists use photography to depict communities with everything from empathy to criticism.

Seen through the lens of the artists

Portrait photos enable us to show our unique personality. But photography can also highlight our similarities and the things we have in common.

Many artists point the camera at our various communities. With humour, empathy, critical awareness or deliberate soberness, the artists push the individuals into the background, prompting our commonality to emerge.

Sometimes artists work with self-staging, challenging stereotypes with their own bodies. For example, they may express ideas about gender, national identity or subcultures in everyday life.

Pekka Turunen

For the series Against the Wall, Finnish photographer Pekka Turunen took pictures of his compatriots in eastern Finland. Humorous and down to earth, the portraits show scenes of daily life in the countryside, where traditional modes of living are under pressure after fifty years of rapid and massive urbanisation.

Walker Evans

Walker Evans photographed fellow passengers in the subway with a camera hidden under his jacket. The results were keenly sensitive and ruthlessly honest portraits of people who, unaware of the photographer and with their guard down, are deep in conversation, lost in their own thoughts or observe something with rapt attention. The pictures offer us a stealthy look at how we behave in public places when we are not posing for a picture.

Photo: Walker Evans

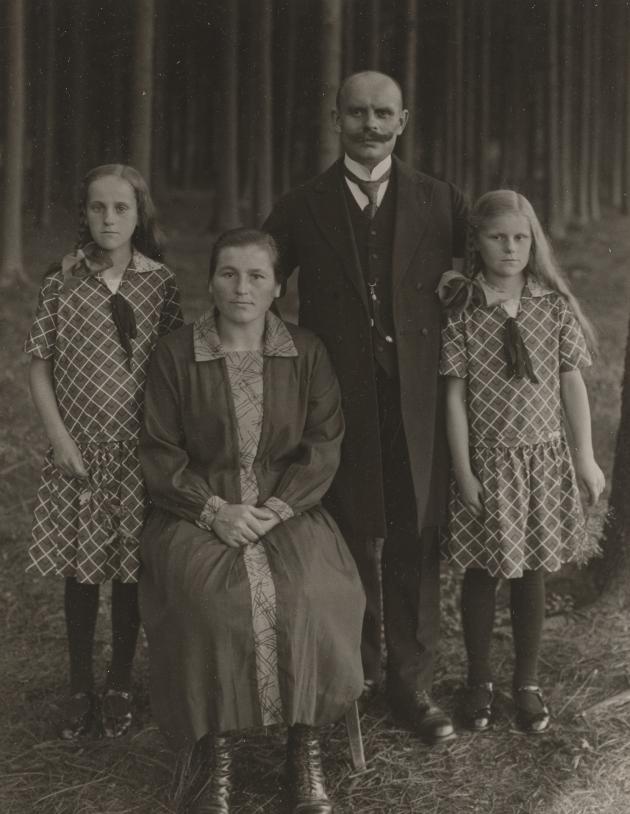

August Sander

August Sander photographed German citizens across established divides of geography, class and age. From farmers to architects, students to doctors. The photographer’s goal was to paint a picture of twentieth-century man, not on the basis of race or nationality, but on professions. Featuring sixty of his portraits, the book Antlitz der Zeit (The Face of Our Time) was published in 1929, serving as a kind of encyclopaedia of human types. It shows an essential shared humanity despite all differences and diversity.

Photo: August Sander

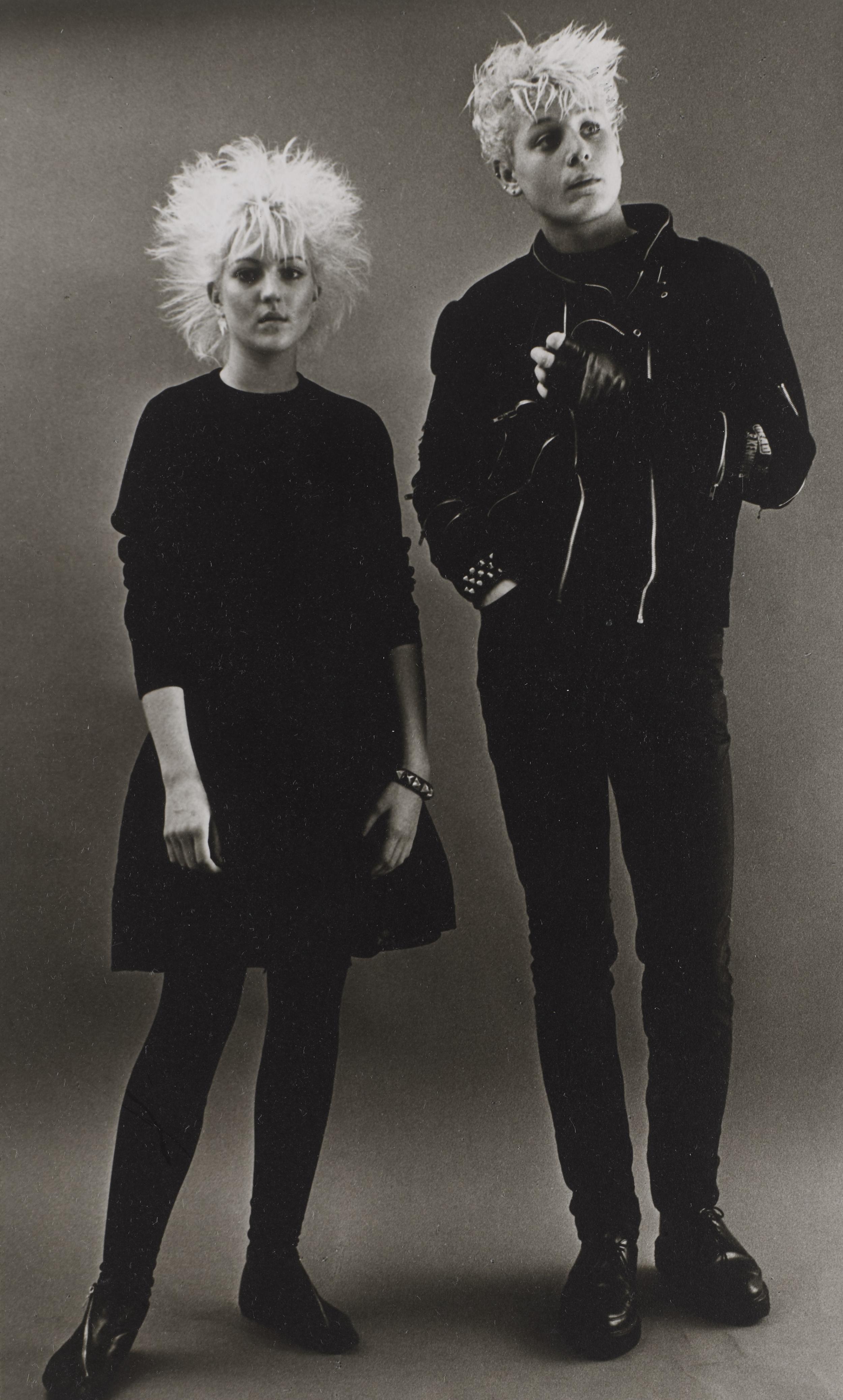

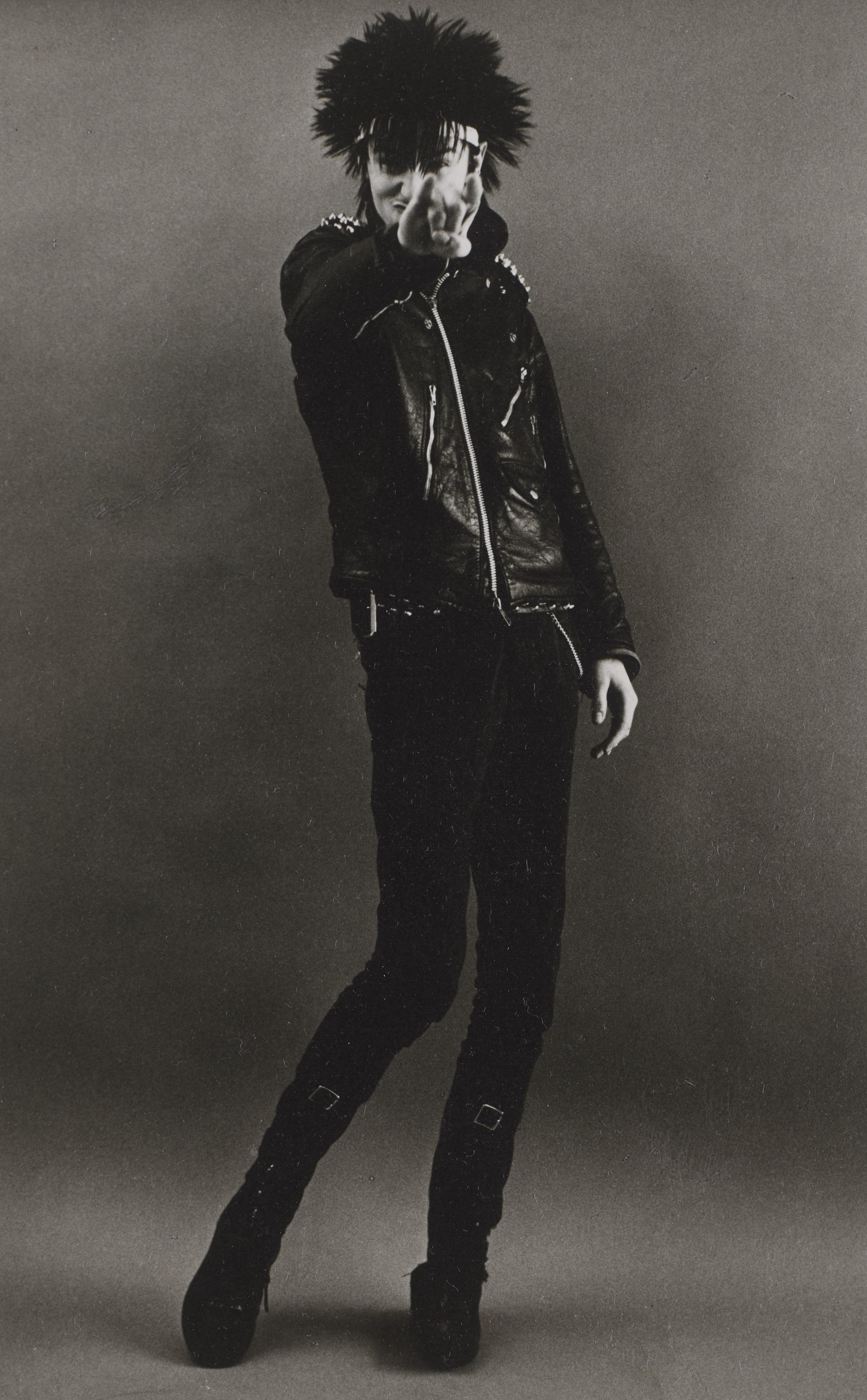

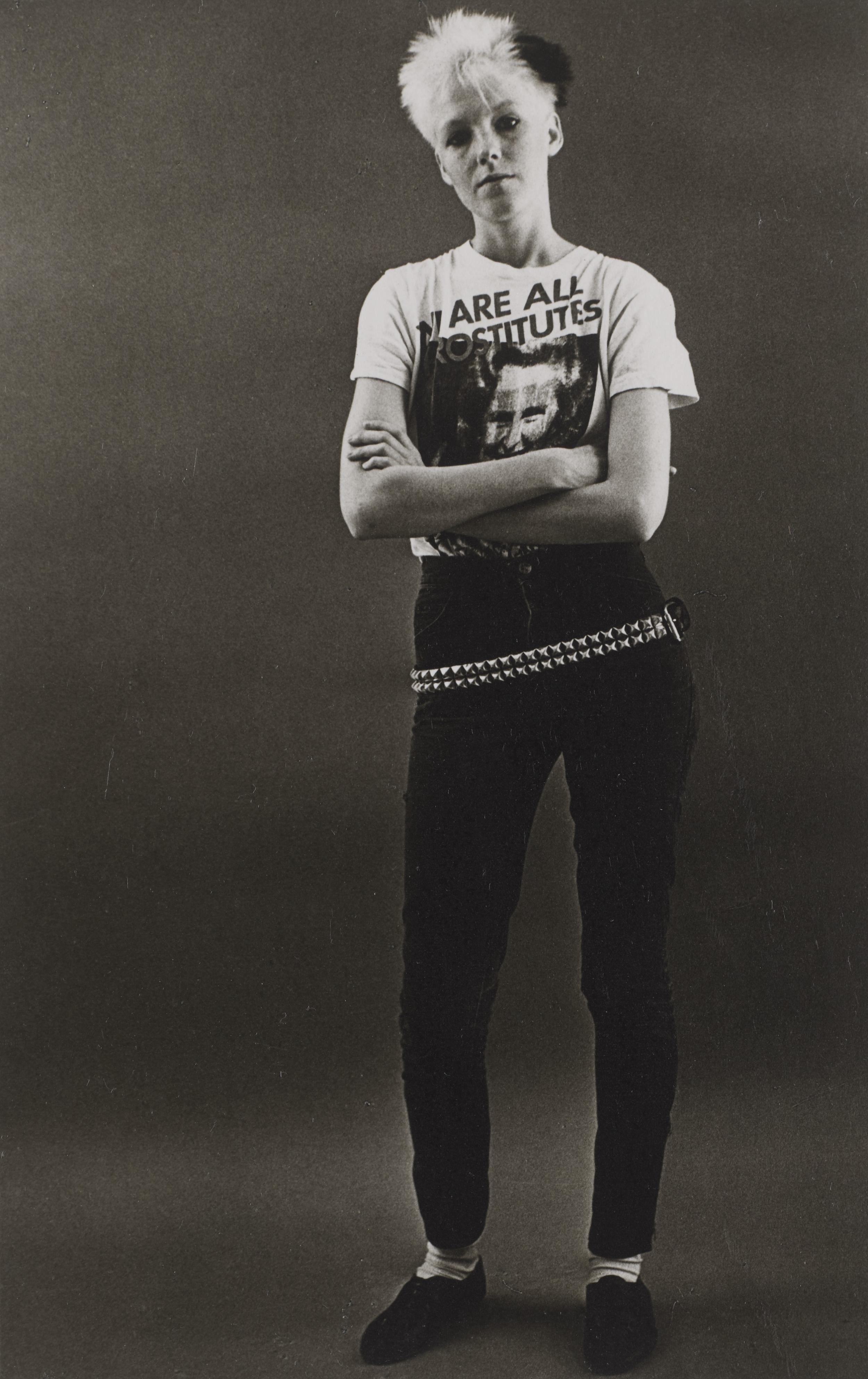

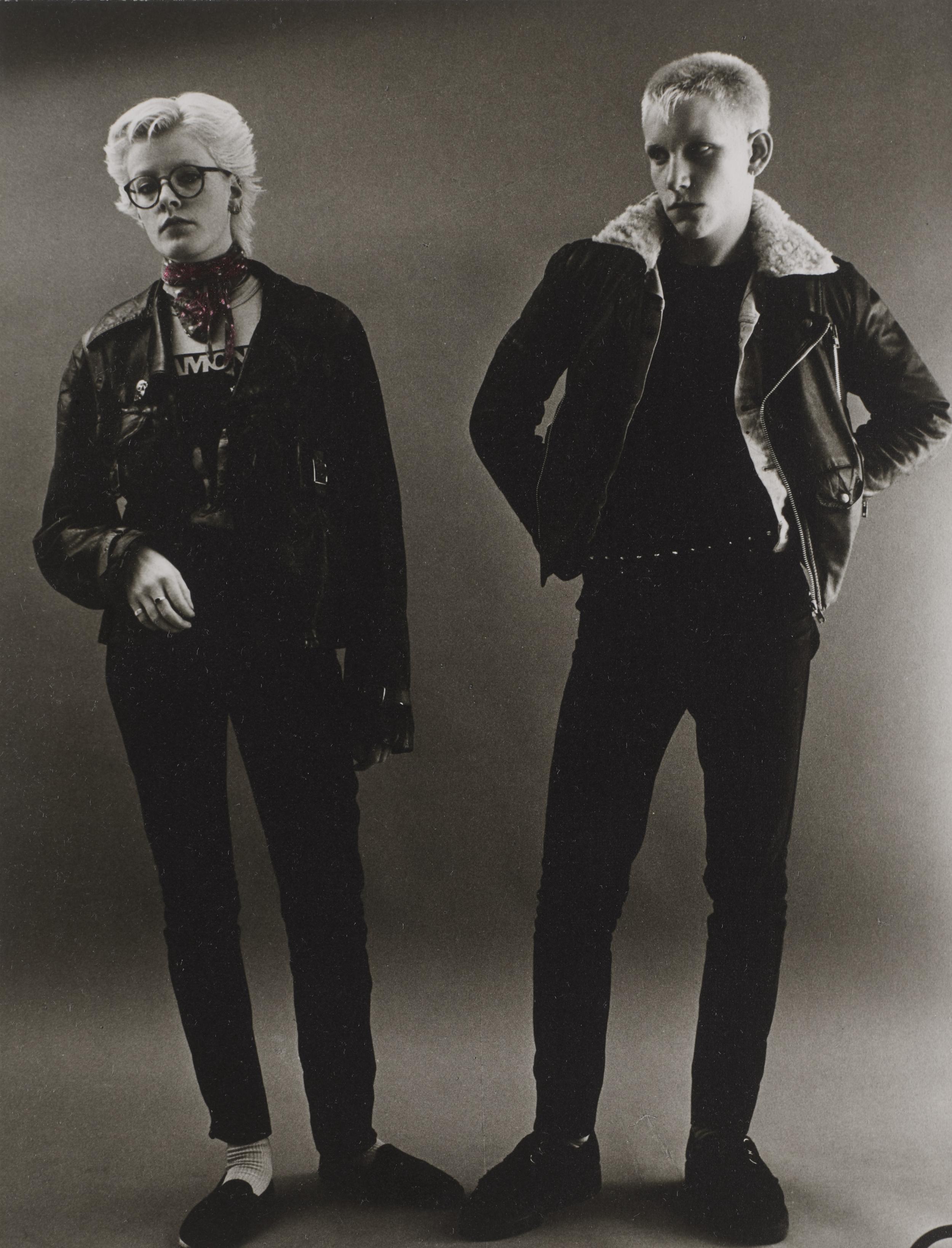

Tove Kurtzweil

In 1981, Tove Kurtzweil had a studio in Kattesundet in Copenhagen, a neighbourhood where many punks hung out at the time. In the series, Kurtzweil soberly yet sensitively portrays the young people as members of a distinctive group. The images resonate with youthful vulnerability, and at the time the stylised aesthetic makes them appear as types: the clothes, the hair, the piercings and the attitude bind them together as representatives of the punk movement’s rebellion against established society.

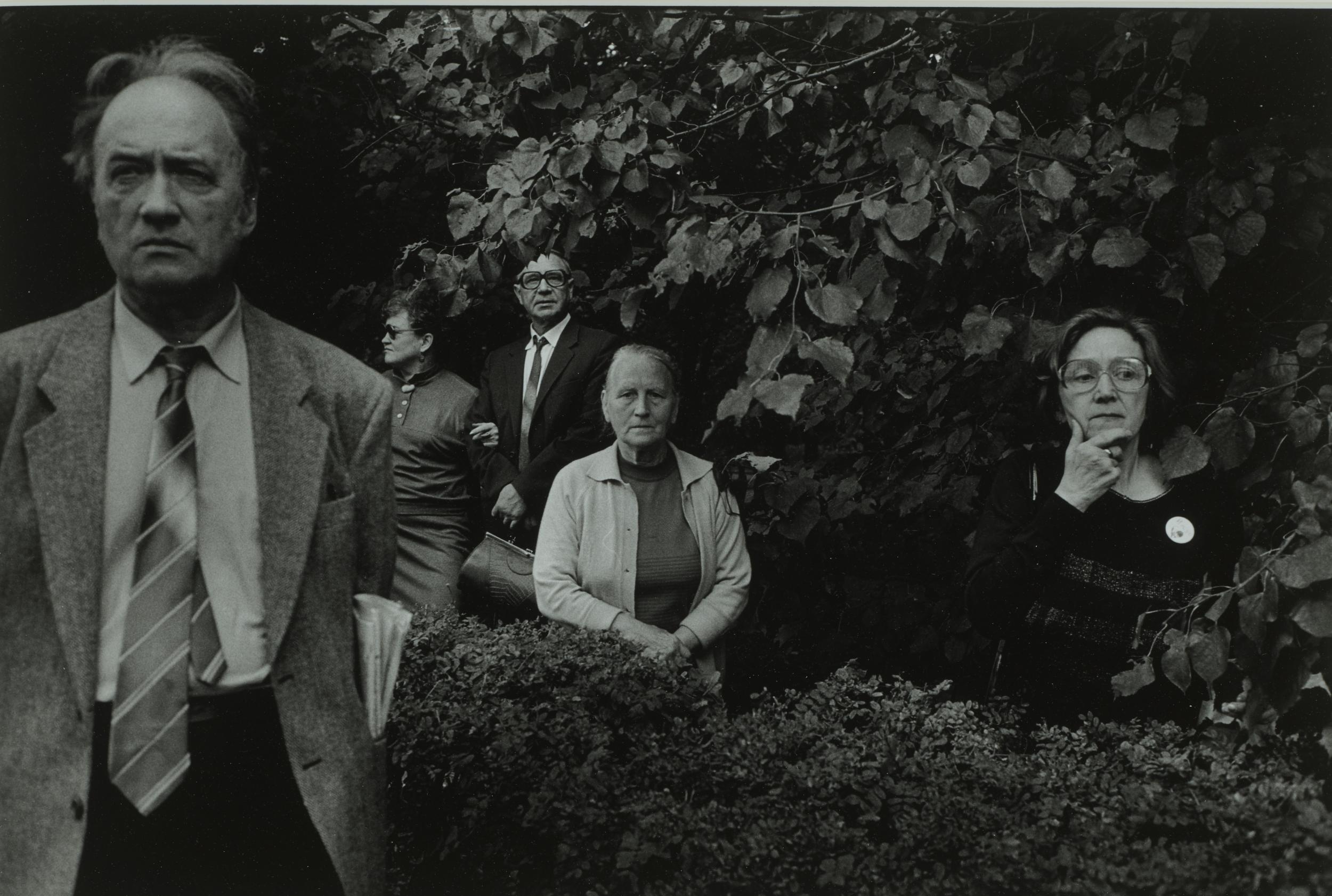

Krass Clement

On 24 August 1991, Krass Clement turned his camera on a group of people standing still in the Krasnaya Presnia Park in Moscow. They were watching a funeral procession in honour of three victims of a failed coup. Clement was in Russia on behalf of the newspaper Weekendavisen, but his pictures are not reportage in the usual sense. Instead of pointing the camera at the procession, Clement took pictures of the people who were spectators to this historic moment – some with their eyes fixed on the procession, others with their attention turned to the camera.

Trine Søndergaard

Trine Søndergaard’s series Strude portrays women and girls clad in historical costumes. The impersonal depiction presents them as types, generating a sense of distance and alienation. The effect is enhanced by the fabric masks worn by some of the women. Known as a strude, such masks were used by the women on Fanø during field work to protect their face from wind and weather. The mask went out of use around the year 1900, and the old costumes eventually ended up as festive folklore.

Photo: Trine Søndergaard

Pia Arke

In Pia Arke’s self-portrait depicting her with a kamik on her head, the boot is not alone in being turned upside down – so too are many concepts. The artist plays around with the prejudices with which she, being half Greenlander and half Dane, was often met. Such preconceived notions were often associated with ‘ethnographic’ props such as kamiks or kayaks. By wearing a kamik on her head, she parodied the ethnographic recordings and stereotypical representations of Greenlanders seen in photographs from the early twentieth century.

Photo: Pia Arke

Jeannette Ehlers

Jeannette Ehlers’s video installation features slow transitions between images of different women, causing them to flow into each other and giving rise to what may be described as a single, communal body. On the wall hangs a copy of a picture from the Royal Danish Library’s collection of pictures from the former colony of the Danish West Indies. It shows Sarah, who was a housemaid in the employ of a Danish pharmacist. In the audio track accompanying the video, the poet Lesley Ann Brown recites a text addressed to Sarah: ‘You are a possible me in the past, I am a possible you in the present … with a sea of time between us’. The words evoke a sense of community centred on the experience of racism shared by the women in our present and Sarah from the past.

Photo: Jeannette Ehlers

Arvida Byström

Swedish artist Arvida Byström’s favourite medium is Instagram. In her works, she engages directly with selfie culture and the ways in which gender, body and identity are portrayed on social media. Digital photography and the mobile phone camera play a pervasive role in the Internet’s impact on our lives today. This forms the starting point when Byström explores and lambasts, with humour and keen incisiveness, the dominant beauty and body ideals on the internet – complete with hairy legs and armpits.

Photo: Arvida Byström

Nicolai Howalt

Nicolai Howalt’s series Boxers consists of double portraits of boys taken just before and after their first boxing match. The boys have been photographed facing us directly, adopting the same pose in both pictures. This makes the changes very noticeable. We do not see the actual boxing match, and yet everything that has happened during the minutes elapsing from the first to the second picture comes across very clearly. At the same time, the photos can be seen as pictures of the development from boy to young man.